Lipstick Under My Burkha – Is it revolutionary?

The highly anticipated film, Lipstick Under My Burkha only shocks because it puts to screen unfulfilled desires of women in India, as rape and oppression are commonplace, mundane realities in their lives.

Lipstick Under My Burkha released on July 21 and reports on its box-office performances remain optimistic. The film was eagerly awaited owing to the controversy it was mired in with the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC), initially facing a denial in certification and later granted one after a legal dispute. The movie, refreshing as it was hardly revolutionary except in its attempt to showcase the daily struggles women face in exploring and expressing themselves.

Lipstick Under My Burkha, directed by Alankrita Shrivastava has received more than 10 awards internationally, even as it fought a hard battle to be passed by the CBFC, nicknamed the Censor Board of India. CBFC unapologetically stated the reason for the initial refusal for certification, calling the film ‘lady oriented, their fantasy above life. There are contanious sexual scenes, abusive words, audio pornography and a bit of sensitive touch about one particular section of society.’ Undoubtedly, such a wild and enticing description built up the hype around the film, which finally achieved certification and was released on July 21.

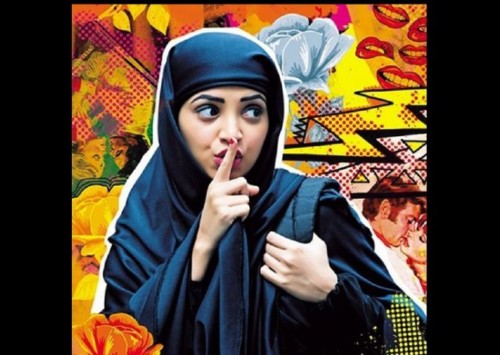

Watching the film, one can hardly stop themselves from wondering about just what was so revolutionary or radical about the film’s portrayal of women, sexuality and society that stirred up the CBFC’s nest on one hand and the heaps of accolades and appreciation it has thus gained on the other. Perhaps the answer lies in the treatment of characters in the film, who dare to do something as unthinkable as dream and desire, sexually and otherwise. The four women are all memorable characters, whether Usha a maternal figure, widowed yet rediscovering her sexuality at an older age, Shirin a homemaker and salesgirl in secret, Leela, a sexually adventurous woman on the verge of a marriage she doesn’t want, or Rehana, a college student who hides away her burkha in public and portrays her love for pop music.

In opposition to women in reel and real life are expected to be in India even in the 21st century, their characters decidedly painted as per a patriarchal brush, this film manages to break the norm in some ways. However, one is left with the feeling of despair at the last scene of the film, when the ‘revolution’, carried out by protagonists Ratna Pathak Shah (Usha), Konkona Sen Sharma (Shirin), Aahana Kumra (Leela) and Plabita Borthakur (Rehana) in their secret, personal lives, borders on the line of becoming yet another patriarchal stereotype.

It is important to note that despite the attention that the film has received due to its portrayal of sexuality, it isn’t the central idea of this film, nor is it the most imaginative one in terms of treatment. A cheesy, cheap-erotica narrative, read by the endearing Pathak that resembles a watered down version of Mills and Boons, binds the four characters, who, in their individual struggles are united in their quest to express their desires and opinions- something they aren’t too successful in. What is remarkable though is how the regressive and staunchly oppressive behaviours of others around the four women is portrayed sans drama, exaggeration or any form of highlight.

Personal lives as a stage

The horrors of daily lives of women, across age or marital status, as showcased by the film, is perhaps what is then the biggest thing to take from it. As it closes on an apparent open ending, some are bound to feel the rather uninspiring tone that the entire movie follows, in terms of bringing actual change in the public status of women. Time and again, the film reminds us of the consequences of taking a stand as a woman, and also how escaping into a world of dreams or secrecy is maybe the only place that gives scope for expressing oneself as a woman in a small town in India.

As promised, the focus is on the women, though layers and complexity of the characters is hardly explored. Whether marital rape, which is not recognised legally as rape in India, desexualisation of elder, widowed women, reinforcement of the ideal-daughter roles and marriage as a tool for social and economic security, Lipstick Under My Burkha manages to touch upon the undeniable realities of women in India. As far as the ‘feminism’ of the film goes, the film is more entertaining than it is intellectually stimulating. Yet, this film, for the simple fact of attempting to portray women as they are, makes for a powerful symbol. Perhaps it lacks the fire to start the ‘Lipstick Revolution’ it intended to, but it will surely inspire some to dream about the same.