Mandatory local guardian rule of Jamia Millia Islamia sprouts new businesses

Desperate hostel-seeking students forced to pay strangers for fake letters

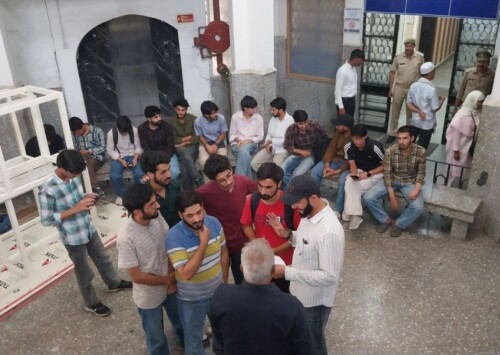

Students at the university which are from outside Delhi are being forced to turn to locals, complete strangers, to act as their local guardians (Photo: JMI website)

A growing number of outstation students at Jamia Millia Islamia are being forced to pay complete strangers some money to pose as their ‘local guardians’ in order to meet the requirement of the institution which now allocates hostel accommodation only to those students with a local guardian.

Students at the university which are from outside Delhi are being forced to turn to locals, complete strangers, to act as their local guardians (Photo: JMI website)

A new rule imposed by Jamia Millia Islamia, a leading university in South Delhi, now makes it mandatory for students applying for hostel accommodation to furnish a letter from a local guardian.

As a large number of students at the university are from outside Delhi, they are being forced to turn to locals, complete strangers, to act as their local guardians.

What was intended to be a support mechanism for students, has instead created a system of dependency, exploitation, and additional financial burden, highlighting the gap between university rules and student realities.

Jamia Millia Islamia admits thousands of new students every year. In the 2023–24 academic session alone, the university enrolled 6,871 first‑year students across undergraduate and postgraduate programmes, 4,052 male and 2,819 female. Around 60 pc of these students come from outside Delhi‑NCR, arriving from places as far away as Jammu and Kashmir, Bihar, Kerala and Northeastern India and even international students, representing over 30 countries.

But since the university’s hostel infrastructure is limited, with about 2,220 places for males and 1,900 for females, only a fraction of outstation and international students can be accommodated on campus. The remainder are forced to find on their own alternative options like paying guest, rented flats, or temporary housing, which is much more expensive and with many other conditions attached, depending on the whims and fancies of the landlords. This makes hostel accommodation a much-preferred option for the students. However, recently, the institute added the necessity of providing details of a local guardian based in New Delhi itself, a condition that a majority of students from outside Delhi are not able to fulfil.

This has left many students stranded in the city until they find someone who can fulfill this requirement. The imposition of this condition has led to a new business opportunity for middlemen who promise to find ‘local guardians’ for the hapless students.

While exact numbers are not available, anecdotal evidence from students and parents suggests that at least some of them are turning to complete strangers through a middleman to find local guardians.

In April, Jamia Millia Islamia reopened admissions, and as every year, thousands came from Kashmir, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand, Kerala and the Northeast. But alongside certificates, photos and fee slips, one new requirement quietly determined who could move forward.

The hostel form demanded a Delhi-based local guardian with signature, Aadhaar card, full responsibility of conduct and availability in any emergency.

When the list of students selected for admission to the university was published, Areeba Mohammad, a first-year psychology student from Kupwara in Jammu and Kashmir, remembers crying out of joy. She packed two bags, boarded a bus to Srinagar and then a train to Delhi, imagining freedom, hostel life and late-night study circles.

What she did not imagine not even once was standing outside Jamia’s admission office for five days, desperately dialling strangers, searching for something she had never heard of before, a local guardian.

“I had everything I needed for admission, including the score, the merit list and the dream. But when I reached Delhi, I realised that wasn’t enough. I didn’t know a single person here, not one. And suddenly I was running around asking people, making calls, looking for a ‘local guardian’ something I didn’t even know I needed. How do you find a guardian in a city that is completely unknown? I wasn’t struggling with studies or merit. I was struggling with the simple question who will take responsibility for me in this place,” Mohammad tells Media India Group.

For students like Mohammad, hope run into a bureaucratic wall. As she wandered around campus, trying to figure out how to fulfill the local guardian requirement, someone told her that there were paid agents who could help find the elusive local guardian for Mohammad.

“I didn’t know what else to do. I called the number they gave me, met the agent, and paid INR 4,000 for the whole year. I had never met them before, and I didn’t know if I could trust them, but I had no other option. I was desperate without a guardian, I couldn’t complete my admission,” she adds.

Raghav Singh, a first-year student from Bhattian in Amritsar, faced a similar struggle when he came for admission. Like many other outstation students, he had no contacts in Delhi to act as a local guardian. He, too, learnt about agents operating unofficially, offering to act as guardians for a fee.

“As the deadline to submit my form was approaching, the agents started asking for even more money. I wasn’t ready to pay that much, and I felt completely stuck. Then someone told me about a guardian affiliated with the university who could act as my local guardian. I approached him, and he agreed to help in return for a smaller fee. For us students, living in a PG or rented flat is expensive, and the hostel is much safer and more affordable. The university started this local guardian requirement to help students, but now illegal agents have emerged, exploiting the system and charging high fees,” Singh tells Media India Group.

No official mechanism exists for students who have no relatives in Delhi‑NCR. There is no campus‑verified list of guardians, no emergency support system, and no alternative documentation route for students to complete their admissions and hostel formalities.

The policy existed on paper but not in practice. For students arriving from distant states, the requirement for a local guardian became an obstacle rather than a support.

Naturally, a workaround emerged. Quietly. Invisibly. Like all markets built on necessity, it filled the gap left by an administrative system that did not account for students without contacts in Delhi.

A senior PhD scholar, who has been observing the admission cycles at Jamia for the last three years and does not wish to be named, explains.

“Whenever a rule is introduced without proper infrastructure or support systems in place, a gap inevitably appears between what is required on paper and what students can actually access. In such situations, a paid substitute often emerges to fill that gap. In this case, the substitute is a local guardian someone students have never met before, who they have to trust to complete official formalities, and whose role exists solely to satisfy the university’s requirement. It is a system built on necessity rather than genuine support, and while it helps students meet deadlines and get their admissions processed, it also opens the door to exploitation and dependency,” she tells Media India Group.

Seven months have passed since admissions and the novelty of a new academic session has faded, but the problem has not. With the release of the new hostel accommodation lists, the pressure has sharpened once again. Hostel rooms are still limited, competition is high, and students without local guardians stand at the weakest edge of the system. What began as confusion has now evolved into routine: the private guardian market operates like a whispered norm, an unspoken system sustained by silence, urgency, and the cost of missing a seat.

Students, knowing that PGs and flats are expensive and far less secure, accept these paid guardians as an inevitable step toward hostel eligibility. Parents, watching from distant cities, surrender to the process because there is no alternative. The university, meanwhile, has neither acknowledged nor regulated the rise of these informal agents leaving the shadow network to grow without oversight.

And what remains at stake is not just paperwork or a signature on a form, but trust, safety, and the right to education without hidden markets operating beneath the official structure.