No Byte in Dance over TikTok

The government’s much applauded ban on 59 Chinese apps, in response to the Chinese aggression in Ladakh, will have minimal impact on China and may also fall foul of WTO rules.

The Indian government’s decision to ban 59 Chinese apps, including the popular short video app Tok Tok, has been hailed by all and sundry across the nation. Some have even termed the action ‘Digital Strike’, drawing parallels with the Indian military’s blitzkrieg in Pakistan that is often referred to as a ‘surgical strike’. Most, including analysts, media reports, government officials as well as the ruling party supporters say that the ban was a very well thought out plan that will significantly hurt Chinese economy.

The Chinese government has spoken out against the ban, not unexpectedly. It accused India of ‘picking out’ Chinese companies and that such targetted bans run foul of the World Trade Organisation rules governing a free trade globally. The Chinese response to the ban has again been played up by many as a ‘proof’ that the ban has already begun to pinch the Asian giant and that with this move China’s global ambitions to dominate hi-tech businesses has received a mortal blow.

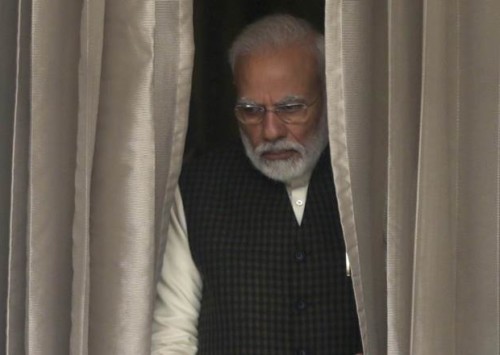

Certainly, the Indian government could not have turned a blind eye to the Chinese aggression and occupation of strategic territory in Ladakh and it had to take some action, not just to send a clear and firm message to Beijing, but equally, if not more, importantly to the domestic audience in India that the government, which has always projected itself as the strongest since independence.

Thus, the Indian leadership picked up a very high-profile, even if soft, target of 59 most popular Chinese apps available in India. By banning these apps, instead of slapping on some additional customs duties on key Chinese exports to India or other such complicated scenario which would not directly impact an overwhelming number of Indians. But by picking up apps that were extremely popular in India, Modi ensured that every Indian knew of it and felt by the ‘muscular’ manner in which India has hit back at its adversary. Of the applications, TikTok is by far the most well-known, which has been downloaded over two billion times all over the world and over 610 million times in India. The short video application has become so popular in India, as in other countries, that it is now the most downloaded app in India and counts over 200 million active users, a hefty figure by any standards.

The TikTok bug seems to have bitten all kinds of people – elderly couples, police officials, bureaucrats, students & housewives. Many have emerged as national stars, with a fairly decent number of followers and made neat sums through advertisements. TikTok cut the enormous gulf between the ordinary people and film stars or the glamour world and gave practically everyone the possibility to become a star, almost overnight.

Thus, a ban on an app of this nature caught the national and global attention, with most reports calling the move a strong setback for not just the apps themselves but also for China’s advance in the Big Tech universe. However, a closer look at the current fortunes of not just TikTok but practically any digital app in India would show that it would be years, if not decades before the Indian market becomes a significant part of the global businesses of Big Tech firms. Currently, Indian revenues for most such businesses are dwarfed even by small EU countries, let alone large economies like the US, China, Germany or the UK. For instance, in 2019, ByteDance, the Chinese owner of TikTok, closed a global revenue of USD 17 billion, while in India, the company could manage a meagre INR 437 million (USD 5.7 million) or 0.03 pc of its global income. Also, the company is growing at over 100 pc a year in India, almost the same rate as it has clocked across the world last year.

Compare for instance, two other large markets for TikTok, US and China. The app made USD 87 million in the US and USD 331 million in China. Not just by revenues, Indian market is still extremely underdeveloped even for generating sizeable profits for any startup as even the most well-established ones like e-commerce site Flipkart or food delivery firm Zomato continue to bleed heavily and are far away from even breaking even. The Indian consumer’s appetite for spending is indeed very limited, especially when it comes to ordinary people all over the country, rather than the select few much-better-off families. Thus, the average transaction size is much smaller.

Let alone such apps, even the modest telecom firms in India have been bleeding heavily over the past decade or so due to extremely competitive market and the low spend per user, making India important only for its volumes but not margins or quality of customers or average transaction size.

It would take decades for India to become a really lucrative market for these apps, but it is very likely that the ban does not turn out to be very long-lived. While currently the tensions between India and China are high, but both the regimes know that they would have to find a way out of the current imbroglio, with neither side losing face, at least publicly. Once a solution is found, the ban is as quickly likely to be removed as it was imposed. In the interim, besides grabbing headlines and being out of the market for a short time, the Chinese apps and indeed any Chinese company, is likely to lose little from the current measures initiated by India.

Until then, one can be pretty certain that China will retaliate, by banning an equally high-profile segment of Indian business in a tit for tat with India. It is not certain, but likely that the Indian ITES firms, already hounded by US President Donald Trump, could come under the scanner of Chinese President Xi Jinping as well.