Privatisation is not the magic pill

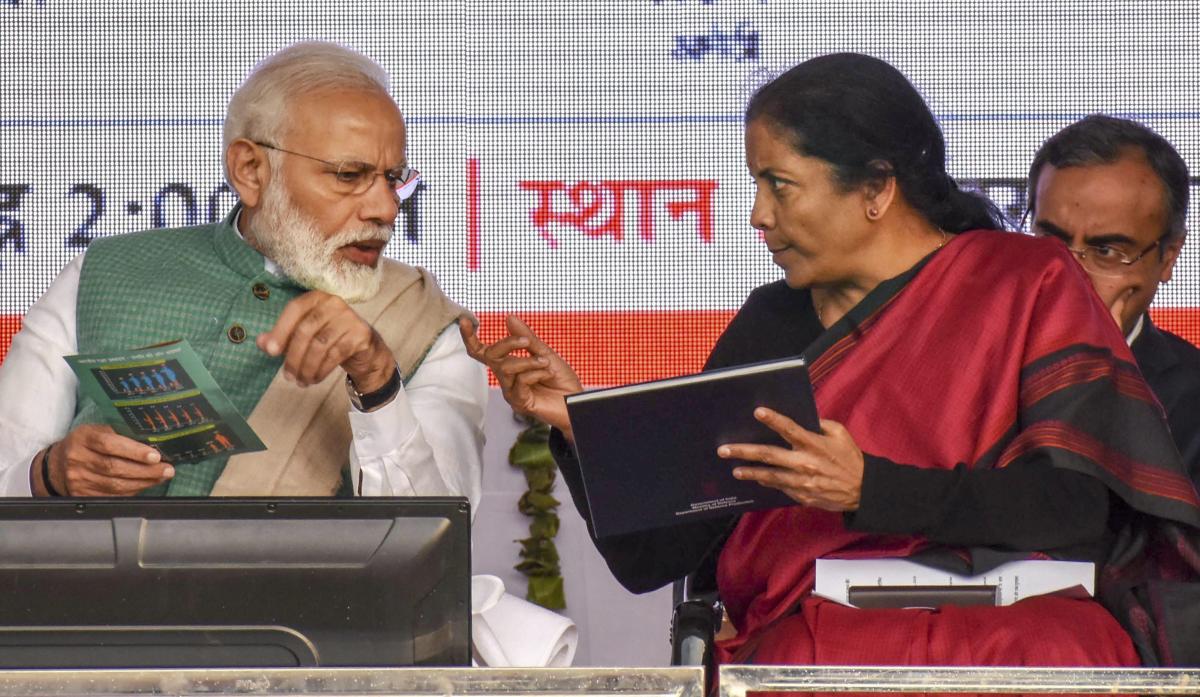

Finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman has said that the government will privatise all public sector enterprises, other than those in strategic sectors

In her budget speech on February 1, union finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman outlined the government’s ambitious plans for privatisation, both in the current year as well as a government policy. She said that the government will privatise all public sector enterprises, other than those in strategic sectors. She did not spell out what constitutes strategic sectors for the government.

For the fiscal starting April 1, 2021, Sitharaman has a plateful of privatisation targets as she committed that the sale of BPCL, Air India, Shipping Corporation of India, Container Corporation of India, IDBI Bank, BEML, Pawan Hans, Neelachal Ispat Nigam Limited will be completed in 2021-22, along with two public sector banks and one general insurance company.

As expected, the announcement received rousing welcome from the business leaders and global financial as well as multilateral institutions, who hailed it as a significant move. However, there was also sharp criticism from labour unions as well as the opposition parties that say Modi government is out to gift the entire country to his capitalist cronies, referring essentially to the Reliance Industries and Adani Group, which are seen to be extremely close to Modi and who have reaped unprecedented riches during the seven years of Modi government.

Sitharaman said that for the government monetising operating public infrastructure assets is a very important financing option for new infrastructure construction. These include a wide range of public assets from roads, power lines, to oil & gas pipelines airports, railway infrastructure and even stadiums.

While indeed the government can exit some sectors, but a wholesale privatisation of public assets is a very dangerous route to take as the past experience in India and overseas has shown. Take the British privatisation exercise, for instance. Margaret Thatcher privatised practically everything from water supply, electricity to railways. Over two decades later, British consumers are paying a hefty price for the haste in which these privatisations were conducted. Private water supply companies have been found guilty of supplying bad quality water at irregular hours and highly overpriced. Ofwat, the water services regulation authority of the country, has already imposed hefty fines, often over GBP 100 million, on many of the privatised water firms for failure to invest in infrastructure, leading to high leakage rates as well as polluting the environment. In September 2019, Ofwat asked Thames Water to refund GBP 100 million to its customers for poor service.

The British experience in privatisation of railways has turned out to be no better as the British commuters regularly complain of extremely poor services, lack of punctuality and extortionist prices charged by the rail firms that don’t keep the rolling stock up to the mark, adding to passenger discomfort.

The problem of private companies faring worse than public is not limited to the UK. One look at the health insurance and the healthcare industry of the United States shows up the challenges that a social sector faces when it is handed over to private firms whose sole objective is to keep their shareholders happy, by giving out huge dividends at the cost of investing in their business or even remaining competitive. Prices always tend to shoot up after privatisation, often without any corresponding gains for customers.

The examples are aplenty around the world and the danger of government exiting or underinvesting in key sectors visible even in India. Take Indian healthcare and education for instance. In both these sectors, the government has consistently under-invested, leading to creation of a large private ecosystem, much larger than the public sector. The sorry state of both the sectors is visible today as Indian students continue to rank well below the global averages in practically every subject and the rising unemployability of Indian youth, armed with degrees that are worth lesser than the paper they are printed on. With poor monitoring and practically no regulation, Indian government has overseen one of the world’s poorest performing education system that is priced beyond the reach of the average citizen.

India’s performance in healthcare is no better. With few public hospitals and practically none that are well-equipped, most of the people have been forced to turn to the private sector which has simply become a money-making machine for its owners as outrageous prices are charged by a sector that has no regulator sitting atop ensuring that consumers get a fair deal. As a result, hospitalisation is by far the single biggest reason for an Indian to be severely indebted. A survey by Public Health Foundation of India said in 2018 that about 55 million Indians were pushed into poverty in a single year due to patient-care costs. The rising cost of treatment, especially in corporate hospitals, is making the life of the citizens difficult. People dread falling sick for fear of falling into a debt trap as about 80 pc of the costs are paid out of pocket.

Monopoly and oligopoly

There are other risks with privatisation as India’s experience with telecom and airports shows. While in telecom, after a messed up privatisation that led to a major brouhaha over a scam that was later found to have never occurred, Indian telecom regulator as well as the Competition Commission of India have overseen creation of a duopoly. First, the regulators turned a blind eye when Mukesh Ambani’s Jio flouted all rules of a fair market and competition to enter and quickly dominate the market by offering free services for a year. They also watched from the sidelines as all the market players fell aside, leaving a very strong duopoly of Airtel and Jio that together command 80 pc market share, while uncertainty clouds the future heavily indebted Vodafone Idea and public sector BSNL which has suffered from government’s negligence to be reduced to penury today.

The story is hardly any better in airport privatisations, another pet of the Modi government. Here, one has seen the emergence the Adani Group, reputed to be very close to Modi, that bagged all the six airports that were privatised last year, even though a group of bureaucrats, overseeing the privatisation, had warned against excessive power going to one company. Over-ruling that, the bids were awarded and recently Adani also gained control over Mumbai airport, the country’s second largest after a perfunctory nod by the government-owned Airports Authority of India. Adani also looks well-placed to bag the new airport in Mumbai that is under planning and could get many more when the next batch of 10 airports go under the hammer, making it the biggest airport operator in the country.

These instances point towards the dangerous trends of crony capitalism at its worst as India seems set to repeat the Russian experience of creating oligarchs with vast business interests covering all aspects of life. The government would do well to pay heed to this, but for the moment, neither Modi, nor Adani or Ambani look stoppable in their drive to bag all that the government can sell off, even if these are large, profitable and well-run enterprises such as oil major Bharat Petroleum Corporation Ltd, the Container Corporation of India or the Shipping Corporation of India.

Globally, public sector or state-owned enterprises is not a four-letter word that the Modi government has made it out to be. Most governments retain a close hand on many large corporations as is evident from Singapore’s Temasek Holdings, which is the investment vehicle of the government, or the French government’s control over a wide variety of French champions such as Alstom or the SNCF. The wonder of China’s economic growth has come about thanks to the Chinese SOEs that have not only done wonders at home but also successfully projected Chinese power and influence around the world.