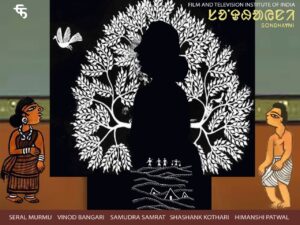

Films of tribal, by tribal & for all: Seral Murmu, filmmaker

Seral Murmu says stories about the forest spirit coming in the form of the tiger had always fascinated him (Photo Credit: Seral Murmu)

Once a shepherd went to graze his cattle in the forest. The shepherd found that a Sal tree had fallen. He uprooted the tree and found some colourful stones beneath in the soil, which he carried back to his home. At night villagers heard the roar of a tiger. Worried, they wondered what had made the tiger roar and began to think that they must have done something wrong. The villagers assembled for a meeting, where the shepherd confessed to finding the stones in the forest which he had carried back home. He was asked to return the colourful stones to the place where he found them. The shepherd obliged. Eventually, the tiger stopped roaring at night.

This is but one of thousands of tales that have been prevalent in the tribal areas of India for several centuries, if not millennia. Seral Murmu says that from these stories, he understood the belief and reverence his people had for the forests. “If you harm the forest, it will give you a warning signal. If you do not rectify your mistake, the forest will make sure you get what you deserve,” he adds.

Hailing from Ghatsila, in East Singhbhum district of Jharkhand, a place known for copper mining, 35-year-old Murmu is a well-known name in the small but growing tribal film industry in India. Murmu has even made a documentary for Film Division of India on ‘Farmayish Culture’ of writing letters to the radio in India and how it is still upheld by the tribes that live in places where television connectivity or electricity is still unavailable. His Marathi documentary named Uroos (2018) was screened at Italy Documentary Film Festival.

More recently, he also won the best script award for his diploma film Sondhayni (2019) at Dhaka International Youth Film Festival. The film portrays the socio-political issues faced by the indigenous tribes living in areas impacted by Naxalite movement. “The film is also a message to those who make claims to the forest, be it government, paramilitary forces or extremist groups. The struggle between these two factions has led to bloodshed of the tribals, who are stuck between them,” he says.

The movie is made in Santhal language which also showcases the tribal heritage, art form and their lifestyle. “Though the language of the film is Santhali, it is not for Santhals only. It is about all tribal groups,” he says.

Murmu says stories about the forest spirit coming in the form of the tiger had always fascinated him. Growing up, he would think of connecting these stories to the present scenario in the tribal belts. “These stories fascinated me and I combined these folklores and made one new story, where if something wrong happens in a forest, it takes its revenge,” he adds.

Murmu says that he had always been a film buff, watching Bollywood movies and it is from there that he got the inspiration to get into film-making. “The dissatisfaction with tribal representation in these films is what egged me to be a filmmaker,” and adds, “During my college days at St. Xavier’s, when I used to watch films, I have always had a problem with the portrayal of tribes.”

Murmu recounts watching a movie where a lead tribal character was shown as a drunkard and abusive to his family. He was dissatisfied with the way the outside society portrays a tribal lifestyle. “I used to think, is it the way you represent a tribal? Even if you watch a hit film like Shalimar (1978) starring Dharmendra, a tribal is shown covered in feathers doing jhingalala (a caricaturist way of representing tribes on screen). Is that our representation? Don’t we have any other voice and other stories,” asks Murmu.

The stereotypical representations of tribes would bother him. “I wanted our people to study literature and cinema. Now, slowly people from the tribal background are becoming part of this medium. They are taking film making as their profession, which is a good thing,” says Murmu.

“I was already a film buff, but when I met with filmmakers Meghnath and Biju Toppo I came to know the cinema is more than Bollywood. I came to know of filmmakers who are making films and raising their voices through this medium. This came as motivation and I was inspired that I would also be able to tell my story to others. Then I joined Film and Television Institute of India in Pune in 2011 where I became more resolute about film making,” he said.

Though he learnt the basics of film making at the most reputed film institute in Asia, Murmu says he got to learn hands on next year when he joined Akhra, a film production house founded by director duo Meghnath and Biju Toppo. Along with making documentary films on tribal issues since 1995 in India, Akhra has also been working in the field of culture, communication and human rights issues of the indigenous peoples in India, in general, and Jharkhand, in particular.

Over the last 20 years Akhra has produced more than 30 documentaries which have been screened screen at various national and international film festivals and received critical acclaim as well as prestigious awards. “If someone asks me what is my first film school I would say Akhra. I got to learn a lot about films from there,” he said.

For Murmu, Akhra was a place where anyone who wanted to write or make films would get much push. He also talks of being influenced by Iranian cinema. “In Iran, despite all the restrictions the films that came out of there were beautiful, be it of Majid Majidi, Abbas Kiarostami.”

At Akhra, Murmu says, he would talk to his mentors and say that he wanted to have a film culture similar to that of Iran since as in India, in Iran, too, filmmakers did not have enough money or resources but still would make good cinema. “I was inspired that even with a small camera and limited resources, I can make films and be a storyteller,” he says.

Murmu is hopeful of independent film-making where people can tell their stories without censorship. Presently, he has two documentary projects with Ram Dayal Munda Tribal Research Institute (TRI), a government-owned institute for research in tribal culture, practices and conservation in Jharkhand. He plans to work on establishing a cinema industry in the state. Murmu also hopes to start a tribal film festival as a democratic platform open for people to come and show their stories and initiate conversation.

Films are not just a medium of entertainment for Murmu. It is an important tool for him to tell the untold stories of his people. “As a tribal, I came from Jharkhand to learn film making and if I am making films just for entertainment, then I feel I am not doing justice to the opportunity. I have got to tell stories. I have a responsibility to return something to my society. I want to be the voice of my people. Till now whatever film I have made I have told stories about my people,” he says.