Tagore’s renunciation of knighthood

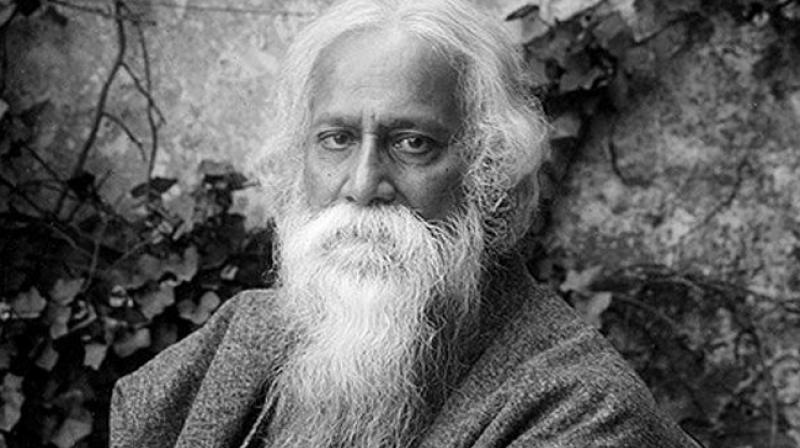

‘Kaviguru’ Rabindranath Tagore has not only enriched literature but also contributed to India’s struggle for freedom. On his 158th birthday, here is an account of one of his action which marked his patriotism in face of the colonial rule.

Poet, author, painter- polymath Rabindranath Tagore, first non-European to be awarded the Nobel prize, celebrates his birthday on Pochishe Boishak (25th day of the first Bengali month of Baisakh) which is also known as Rabindra Jayanti and coincides with May 8 or 9 on the Gregorian calendar. Though according to the English calendar of 1861, his birth date is May 7, the people of Bengal still follow the regional calendar to observe the day with cultural events celebrating Tagore’s life and works.

Tagore was a big part of the Indian revolution during the British rule. He didn’t adhere to petty nationalism as explained in his essay on nationalism and had his own political outlook. The poet could not fully support the moderates because they could not understand the proper Indian culture and on the other hand he felt that extremists were very whimsical in their decision-making which was against the social strategy and heritage of Bengal. He was a humanist and a visionary who wanted to establish policies based on non-violence, spirituality and scientific and logical education. And this he did by denouncing his knighthood as an act of protest after the Jallianwala Bagh massacre.

The Jallianwala Bagh massacre even in its centenary year brings out the same vivid experience of trauma felt on April 13, 1919. The incident completely altered the political scenario and composition of India fighting against the British government. The event caused many moderate Indians loyal to the British rule to abandon their loyalty to embrace nationalist values and grow distrustful of British. Many freedom fighters and political leaders were influenced by the incident too. Tagore’s actions against the cruel act also awakened the non-violent stand against the colonial rule.

Denouncing the knighthood

Tagore during the time of the massacre was ‘Sir’ Rabindranath Tagore (knighthood conferred in 1915) and had been a Nobel Laureate for six years. On receiving the news about Jallianwala Bagh, he tried to arrange a protest in Calcutta (now Kolkata) and finally denounced the knighthood as an act of protest with a repudiation letter to Viceroy Lord Chelmsford dated May 30, 1919.

The detailed information about the incident took time to trickle “through the gagged silence” and reach every corner of the country. Tagore was completely agonised on being updated by CF Andrews, a missionary who had met Gandhi and returned to Shantiniketan. According to Prasanta Chandra Mahalanobis, statistician and founder of Indian Statistical Institute, it was intolerable for the poet who had then sent Andrews to Gandhi with a proposal that if Gandhi agreed, he would go to Delhi and then the two of them will try to enter Punjab. And when both of them are arrested, it would be their protest.

When Andrews returned with a negative answer as Gandhi thought the protest and the subsequent arrest may trigger violence, Tagore was disappointed. He then went to Chittaranjan Das, a leading figure of Bengal during Non-cooperation movement, to arrange a protest meeting which would be presided over by Tagore but even that idea didn’t materialize. So Tagore decided to protest against the brutality by denouncing his knighthood.

He drafted a letter addressed to the viceroy where he wrote that the Jallianwala Bagh massacre had “revealed to our minds the helplessness of our position as British subjects in India.” He had expressed the cruelness of the incident to be “without parallel in the history of civilised governments, barring some conspicuous exceptions, recent and remote.” He wrote, “The accounts of the insults and sufferings by our brothers in Punjab have trickled through the gagged silence, reaching every corner of India, and the universal agony of indignation roused in the hearts of our people has been ignored by our rulers- possibly congratulating themselves for what they imagine as salutary lessons.”

In the concluding part of the letter, Tagore scathingly writes referring to the knighthood, “when badges of honour make our shame glaring in the incongruous context of humiliation, and I for my part wish to stand, shorn of all special distinctions, by the side of those of my countrymen, who, for their so-called insignificance, are liable to suffer degradation not fit for human beings.” A nationalist newspaper had criticised him for taking such risks. Lord Chelmsford did not expect this and even mocked his actions to be dramatic as it didn’t matter to the British rule. However, having known Tagore’s status then in the West and his national presence as the ‘Gurudev‘, his actions could not be ignored by the rulers.

In the August 1920 edition of Young India, Tagore tells his contemporary Indians,”Let those who wish, try to burden the minds of the future with stones carrying the black memory of wrongs and their anger, but let us bequeath to the generations to come memorials of that only which we can revere.”