Indian diaspora in US divided over discrimination

One in two Indian-Americans reported being discriminated against in the United States this past year, especially on the basis of skin colour, says a survey, Social Realities of Indian Americans: Results from the 2020 Indian American Attitudes Survey Indian American Attitudes Survey (IAAS). The report was based on the answers of 1,200 Indian Americans (including citizens, Green card holders and NRIs) and gathered responses over 12 months, roughly around the last year of Donald Trump’s presidency, and in the middle of the coronavirus pandemic.

Mehak Kaur, a 27-year-old PhD student from California, says that although she has not personally faced any serious instances of racism, her father and grandfather, who practice Sikh customs, have experienced racial prejudice in the past. Kaur puts this down to a stark change in attitudes over the last couple of decades.

“Both my dad and grandpa were not chosen for certain jobs because of their turban. There were times when the interviewers said that they would give them the job as long they didn’t wear the turban,” Kaur tells Media India Group, adding, “it was more serious for my grandpa because he moved here a just after (the terror attacks of) 9/11, so he had to face more difficulties as compared to anyone else in the family.”

An interesting analysis in the report commented on the apparent discrepancies between Indians who migrated from India and those who were born in the US. “Somewhat surprisingly, Indian-Americans born in the United States are much more likely to report being victims of discrimination than their foreign-born counterparts,” says the report.

This disparity, however, does not seem that strange to some foreign-born Indians, for example those who have moved to the US for higher education.

“I feel that Indians like me who come here for college or jobs already have an idea in their head that they are coming into a different culture or a different country and people might not understand our accent or way of doing things at first. But if you have grown up here, you obviously expect to be treated as an American because that’s what you are, regardless of how you look,” says Tanya Jain, who completed her undergraduate degree from New York, and now works as a data scientist.

This perception may also be why, as mentioned in the study, “Only four in 10 respondents believe that “Indian-American” is the term that best captures their background.” Aishwarya Sridhar, a second-generation Indian-American, is like the 6 pc represented in the survey who did not like the hyphenated “Indian” part of the term and would prefer to simply be called “American.”

“I understand that my parents are Indian, and I obviously look Indian, but most of my Indian friends like me have only been there once or twice our whole lives. We consider America our home, so it seems unfair that we need to identified as “Indian-American” just because of our skin colour whereas if someone was Caucasian, they would never be questioned beyond just saying that they are American,” says Sridhar.

Kaur thinks the term represents her background quite accurately, but like many Indian-Americans, she faces an identity crisis when confronted with the gap between the two cultures. Although she has lived most of her life in America, she has kept in touch with Indian culture because of her immigrant parents and through regular visits back home.

“I think when you move to a different country, you have a hard time figuring out what your identity is. But even I personally have been struggling to define who I am. I feel like for Americans, I will never be American enough even though I am a citizen and for Indians, I will never be the same Indian anymore. So, it’s always nice to find people who are in the same boat and experience an identity crises just like I am,” explains Kaur.

A “Little India” in the heart of New Jersey (Photo: Jim Henderson)

This is also a big reason why she believes many Indian-Americans look for tight-knit communities wherever they live. According to the study, Indian-Americans tend to socialise mainly with each other, and religion plays a bigger part in this than either region or caste. About 27 pc of the respondent said they attended religious services at least once a week, and three quarters said that religion played an essential role in their lives. Moreover, it also said that Indian-Americans exhibited high rates of marriage within their community, which could be an attempt to hold on to and pass on Indian culture and customs to future generations.

“Los Angeles has a big Sikh community. There are about 3-4 gurdwaras where my grandparents like to go. I believe it’s really important to have a sense of community and belonging especially when you are away from your country of origin and culture. The community plays a huge role in my grandparents’ life because they are both very religious and they both do not speak fluent English. So having people that understand you makes a huge difference to them,” says Kaur.

Along with the harmony and sense of belonging that comes with being a part of the Indian-American community, another important point that the report made was about the polarisation of political beliefs, saying ‘‘to some extent, divisions in India are being reproduced within the Indian-American community’’. The report compares the division in American society between Democrats and Republicans to Congress versus BJP supporters in India, and concludes that “the currents coursing their way through the Indian diaspora are perhaps reflective not only of broader developments in American society but also—and perhaps even to a greater extent—the turbulence afflicting India.”

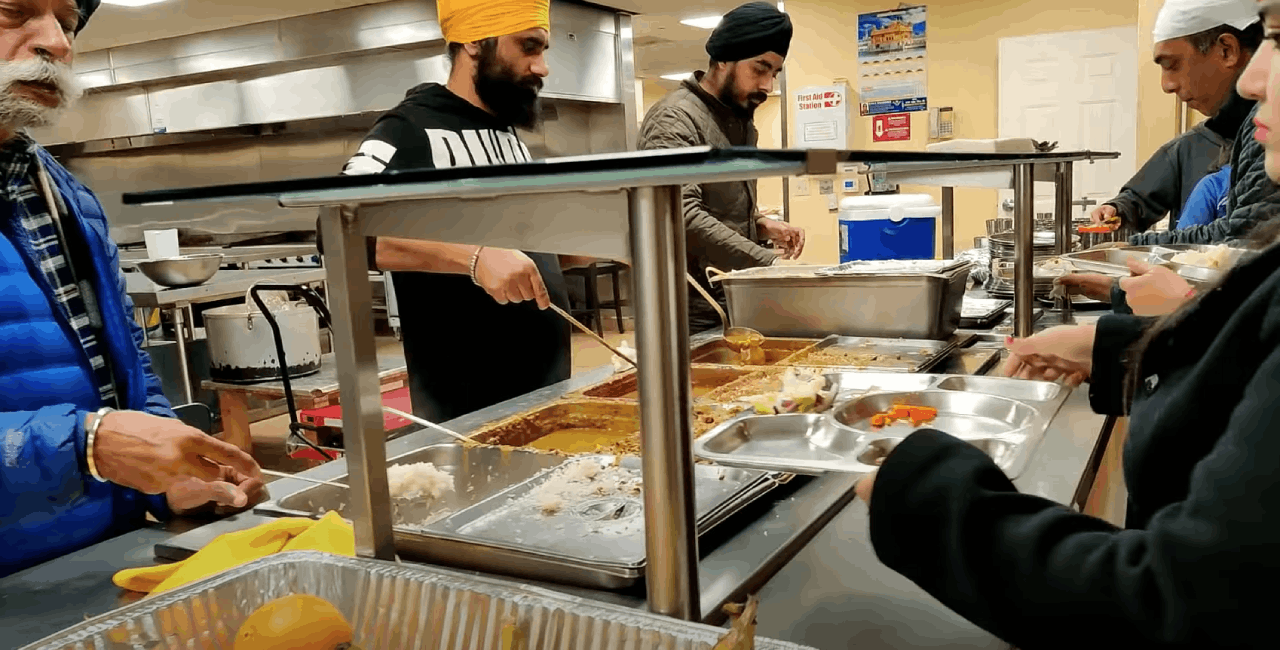

Langar services inside a gurdwara in San Jose (Photo: FoodyVishal)

Although the two main Indian political parties are not as strongly juxtaposed as American political parties, Kaur believes that with Trump’s presidential run, these issues have gained greater traction among the Indian American community. Although she disagrees that differences in religious or political beliefs cause serious conflicts within the community, she explains that citizens are definitely concerned about issues back home, especially if they are able to relate to them.

“The general consensus in my immediate and extended relatives here is that we do not agree with Modi’s policies and we all believe that India has been consistently doing poorly ever since he came into power. The religious polarisation and oppression of the minorities has been one of the most concerning issues for all of us here. Sikhs are a minority in India so it hits home for us. We are concerned that India is moving backwards and we are losing our great democracy because of certain government policies,” says Kaur.

This polarisation may have become more pronounced during the 2020 elections, as Trump became the first American president in almost three decades to lose re-election after serving only one term. The report added, “While religious polarisation is less pronounced at an individual level, partisan polarisation — linked to political preferences both in India and the United States — is rife.”