One of the biggest and oldest travel companies in India is set to go into liquidation amid concerns over governance and transparency.

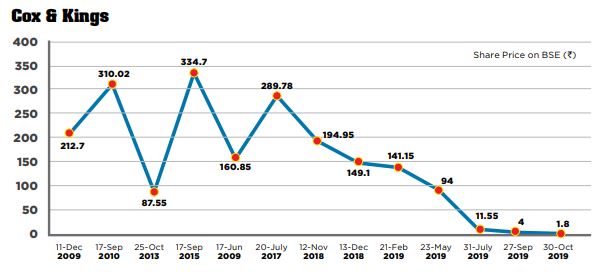

On October 24, as the Bombay Stock Exchange, Asia’s oldest stock exchange closed business for the day, shares of Cox & Kings (C&K), one of the biggest travel companies on Indian bourses, closed at a fresh historic low of INR 2, having lost almost 5 pc during the day. The share price has declined consistently over the past six months and is now over 99 pc below its two-year high of INR 215, putting the market capitalisation of the company from nearly USD 1 billion to below USD 4 million.

Founded 260 years ago, Cox & Kings has been an important part of Indian tourism industry for centuries and one of the leading brands in the sector. Over the last three decades, the company had gone into a massive expansion drive, opening offices across the globe as well as acquiring companies in various parts of Europe. Thus, the company’s sudden bout of troubles did catch the industry by surprise.

Cox & Kings

On May 21, 2019, Cox & Kings announced that it had signed a contract to open its fourth hotel in Marseille, France, as part of its expansion strategy. The deal, made by its subsidiary, Meininger Hotels, took the number of its beds in France to over 2,600. Meininger currently operates more than 26 hybrid hotels in Europe with a total of 3,977 rooms and 14,225 beds in 15 European cities.

And barely two weeks later, in June, when the company failed to honour the repayment of a relatively small loan of INR 1.5 billion, the market was caught unawares. The management blamed the loan default on a momentary cash flow problem and assured the stock market and its investors that all was well and the company’s financial health robust.

However, less than three weeks later, C&K again defaulted on yet another loan and this sent the alarm bells ringing, not just amongst its lenders, which included several leading banks, but also its shareholders and eventually its suppliers as well as employees. In less than a month, C&K defaulted four times and the series of defaults continued right up to October.

The defaults did leave the market and the stock analysts clueless about the reasons behind the default. Most analysts say that the first default of INR 1.5 billion occurred in June 2019, just three months after the company had declared having a cash balance of INR 7 billion. The company generates most of its revenues from sales to different companies controlled by the Kerkars. It stood at nearly 88 pc of its total revenue from operations of INR 27.5 billion in 2018-19 and in the previous year the ratio was even higher at about 93 pc.

Moreover, the company has seen its dues from its clients, besides the promoter family, rising sharply and combined dues for the last two years from this segment were four times the revenues earned by C&K from non-promoter controlled entities. In its annual report of 2018, C&K blames the rise in dues from nonrelated companies on the economic decisions taken by the government such as demonetisation in 2016 and an unplanned and bad implementation of GST or the uniform tax code barely a year later.

On October 15, the National Company Law Tribunal admitted a plea by a creditor of C&K, to start insolvency proceedings against C&K for defaulting on a loan. The proceedings cast a huge cloud about the viability of the company and its future, even as a series of bad news had flowed out of C&K’s office at Turner Morrison building, a landmark Victorian building in south Mumbai.

In September, the company informed the stock markets that the International Air Transport Association had terminated its licence to issue air tickets and also to surrender its IATA card. In the same month, C&K sold its corporate travel unit for an undisclosed sum and in October, the company’s chief financial officer resigned due to ‘personal reasons’.

C&K’s meltdown has shaken up the travel industry as its impact is being felt not just in India, but also overseas. Experts say that the bankruptcy is bound to negatively impact foreign direct investment in travel sector in India as most investors have lost faith not only in C&K, but the entire travel industry in India. ‘‘Cox is a very big brand and name in the industry for many overseas vendors, it was a reference for the outbound travel industry from India. Hence, now that many vendors are facing problems such as delayed payments, they are afraid to deal with even other travel companies from India. Their thinking would be that if a company like C&K cannot be trusted, then who in India can be?’’ remarks the chairperson of a leading DMC in the Middle East that has a fair amount of dealing with numerous outbound travel companies from India.

Many foreign companies that dealt with C&K say that the meltdown has left a very bad taste in the mouth for them. ‘‘We had been dealing with them for nearly two decades and on multiple products of ours. Since July we began to notice a slack in their payments and finally, we are left with a large unpaid bill, which I am sure will remain unpaid,’’ says the manager of a very large European travel company several of whose products were used by C&K.

The company says that while it may have little choice than writing off C&K’s bills, but adds that its dealings with other Indian travel companies will definitely be impacted by the C&K fiasco. ‘‘We will definitely be more vigilant in taking payments from Indian companies and not extend them credit as was done with C&K. If such a big name can sink without warning, then who can we trust in India,’’ he says.

Many destinations have also issued advisories to their partners back home about the problems at C&K and advised them to take immediate steps to protect their interests and minimise their exposure to C&K. While many other smaller travel companies from India may have lost out due to the feared contagion effect, C&K’s bigger rival, Thomas Cook India, is believed to have benefitted from the troubles at C&K as many of smaller tour operators who were using C&K to send their clients overseas turned to Thomas Cook. ‘‘Thomas Cook stands to gain handsomely from the crisis at Cox & Kings,’’ says an industry insider, who, too preferred to remain anonymous.

Over the last few months as the company’s financial health deteriorated, C&K was obliged to cut corners and this resulted in dilution of service levels and outright cancellations of some parts of the itineraries, leading to a number of complaints by consumers, some of whom went to the court.

In July, as C&K defaulted on yet another loan, this time with private sector lender, Yes Bank, the latter encashed the nearly 19 pc stake that the management had kept as a secured guarantee with the bank. This took Yes Bank’s total holding in C&K to over 21 pc, making it the second-largest shareholder, after the promoter group itself.

Despite several telephone calls as well as emails, seeking a response, C&K did not comment on the issue.

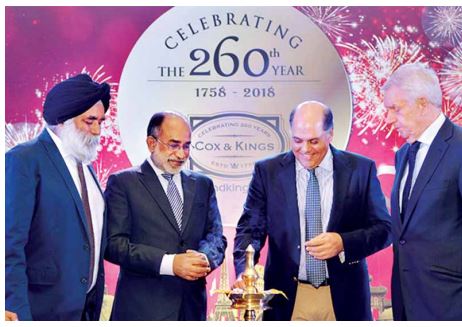

Peter Kerkar (second from right), group CEO, Cox & Kings, lighting the lamp to commence the celebration of Cox & Kings’ 260th anniversary in Delhi in 2018

Governance issues

At the time of independence in 1947, even though the British left India, Cox & Kings stayed on, as did many other businesses run by the British. The current management, Kerkar family, took a significant stake in the Indian business of C&K in 1981 when Ajit Kerkar, father of the current CEO Peter Kerkar, purchased 60 pc shares in the Indian venture. In a way, the governance issues began at that stage itself as Kerkar’s share purchase was made on behalf of Indian Hotels Company Limited, which runs Taj Hotels, one of the biggest clients of C&K then. Kerkar, who was the MD of IHCL, and some of his colleagues in the senior management had bought the stake on the company’s behalf to circumvent the competition rules which would have prevented IHCL from owning Cox & Kings.

The Kerkars managed to keep the stake with themselves even years later when Ajit Kerkar left IHCL and floated his own venture. Soon afterwards, he figured in yet another controversial deal in 2002 when his company Tulip Hotels won a deal to buy Centaur Hotel at Juhu, owned by Air India as part of the divestment process. Tulip’s acquisition was made under very murky conditions and sale price of INR 1,530 million for an iconic, sea-facing six-acre property, with nearly 400 rooms, was considered a giveaway. Incidentally, Kerkar was not only the owner of Tulip and hence the bidder, but he also was a board member of the Hotel Corporation of India (HCI), the subsidiary of Air India that was selling the property. Thus, Kerkar was the buyer and the seller (at least in part) of the same property.

Not just that, according to subsequent investigations several rules governing the buyout were tweaked, twisted or simply broken to allow the deal to go through, believed to be pushed at the behest of the then minister in charge of divestments. That became even more glaringly evident within a year or so, when Kerkar began the process to hawk the property to another firm for a much higher sum. Tulip appointed consultancy firm, Ernst and Young, to ‘assist in divesting equity stake in the company to financial and strategic investors’. Tulip was close to clinching a deal with the French hotel chain, Accor, which was keen to gain a foothold in the Indian market.

If the deal had gone through, Kerkar would have walked off with over INR 3,500 million as compared to INR 1,530 million he had paid for in purchasing the property. Even though it did not come through, by March 2005, Tulip had signed a deal with a Mumbai-based realty firm to sell Centaur Juhu for the same price of INR 3,500 million. The buyer did pay close to INR 1,000 million, but unfortunately for Kerkar, before the balance payment could be made, the government launched an investigation into the original divestment deal and this scared the Mumbai-based buyer, who moved to cancel the deal and withheld the payments, pushing the matter to arbitration. Six years later, the arbitrator terminated the agreement and by now C&K was also a significant stakeholder in Tulip, with nearly 31 pc stake, while Kerkar and his family owned another 22 pc. And the company had retained the injection of INR 1,000 million from the aborted sale deed.

Experts and players in the Indian travel industry say that the Centaur hotel deal were used to buy several assets overseas, though for the Kerkar family rather than C&K. In the meanwhile, C&K was continuing headlong into rapid expansion, a strategy that Peter Kerkar had put in place right from the time that he joined his family business in 1986, straight from his graduation at Standford College in the United States.

Expansions and acquisitions

Kerkar had joined Cox & Kings’ London office as its general manager. The business was not doing well under the franchisee model with partners and Kerkar’s mandate was to clean up the mess. C&K then had three divisions—air cargo, business travel and leisure travel. Kerkar closed the cargo division and focused on purely business and leisure travel. He opened an office in the US, approached travel companies and guaranteed competitive rates by tying up with them. The moment Cox & Kings got scale, he terminated the alliances and started growing on his own.

According to industry old timers, one of the key decisions that changed the fortunes of C&K back at the turn of the millennium was the call to launch outbound travel packages, catering to the wealthy Indian clientele. The call was taken by Urrshila Kerkar, Ajit Kerkar’s daughter and Peter’s sister who had just joined the company.

The move was indeed smart as by the turn of the millennium, airlines began cutting and eliminating travel agency commissions, C&K evolved into a company selling much more than airline tickets, developing complete holiday and tour packages, not just for the inbound travel, but more so for the outbound as a rapidly growing Indian economy sent the number of Indians holidaying overseas into an entirely different orbit.

The siblings also diversified the product marketing from just English to several Indian languages including Malayalam, Tamil, Gujarati and Marathi. Kerkars had adopted an ambitious expansion strategy through the establishment of franchisee shops across India, with the plan to have a presence in all primary, secondary and tertiary locations in the country. And the expansion paid off, at least initially and in terms of topline figures or the overall revenues. Soon, C&K was in the top league of Indian outbound travel companies, along with Thomas Cook and Kuoni. Education tours, targeting students from very well-to-do families for trips to various countries, with a visit or two to some school or university thrown in, was another major new business area where C&K entered and established itself as a leading player rapidly.

By 2009, with the Indian stock markets booming thanks to a record spur of sustained growth, Kerkar took C&K to the stock market through an Initial Public Offering. The boom in the market meant that the Kerkars were able to raise over USD 100 million through the offering. Within months of the IPO, C&K went on a buying spree, acquiring eight companies in Europe and Australia for nearly USD 600 million, of which nearly USD 400 million were spent in buying UK-based Holidaybreak and the German hotel company, Meininger.

The acquisitions added to the complex ownership structure of C&K India and its numerous subsidiaries, clouding the transparency of not just the listed company, but indeed the entire group and its various subsidiaries across the world. The first worrying signs about this rather opaque management came soon after the acquisitions and when they failed to perform anywhere close to the predictions made by the Kerkars at the time of acquisitions.

The buying spree was mainly funded through debt and as a result, C&K found itself heavily indebted by the end of 2014. And by next year, the load began to show as not only did the management have to write off nearly INR 7.5 billion in goodwill, but also reported a net loss for the listed company. The company says it will sell off some of the assets to raise money and cut its debt to more manageable levels. However, its options are limited as it may not be able to get buyers or at least the right price that it may seek for the assets. Moreover, the state of Indian economy, now growing at its slowest in half a decade, will hurt C&K’s revenues and its receivables could continue to mount.

Besides the vendors and investors, the fate of the thousands of employees of the company and its subsidiaries as well as its franchisees remains unclear in the absence of any information coming from Turner Morrison building.

Despite several attempts to contact the senior management of the company, no response was available from Cox and Kings or its representatives to the questions raised in this article and the several others being asked by its shareholders, vendors and employees, in India and overseas.