Uproar over SC ruling on Aravallis intensifies

Environmentalists warn of catastrophic impact on north-western India

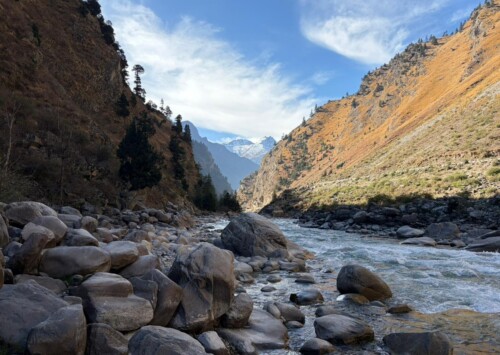

The Aravalli ranges have been described as the “lungs of Delhi” (Photo: Media India Group/Aman Kanojiya)

Supreme Court’s decision to accept the government’s new definition of the Aravalli range has sparked widespread protests across North India, with environmentalists warning that the move could weaken protections for one of the world’s oldest mountain systems and trigger widspread ecological damage.

The Aravalli ranges have been described as the “lungs of Delhi” (Photo: Media India Group/Aman Kanojiya)

A wave of protests has erupted across North India as citizens and environmentalists unite against the Supreme Court’s decision to accept the proposed move of the Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change (MOEFCC) that removes protection from an overwhelming proportion of the oldest mountain ranges of the Indian subcontinent.

From Rajasthan and Haryana to online platforms, the slogan Save Aravalli has gained momentum, with protestors urging the government to prioritise environmental protection.

At a time when New Delhi is grappling its worst-ever emergency over hazardous air quality, the court’s decision has intensified concerns over ecological safeguards.

On November 20, acting on recommendations from the MOEFCC, the Supreme Court introduced a new definition of what constitutes the Aravalli hills, a move that has alarmed environmental experts and conservationists.

Also Read WWF India: conservation starts with education

Under the ruling, any landform located within Aravalli districts that rises 100 metres or more from the local relief, along with clusters of such hills within a 500-metre radius, will be classified as part of the Aravalli range. Critics argue that this marks a significant shift from earlier interpretations, which viewed the Aravallis as a wider, interconnected ecological system rather than a narrowly defined topographical feature.

Starting near New Delhi, the Aravallis stretch approximately 670 km in South West direction through southern Haryana and Rajasthan and terminate in Gujarat. For decades, the Aravallis have been described as the “lungs of Delhi” due to their role in acting as a natural barrier against dust-laden winds originating from the Thar Desert in the west.

The ranges also play a crucial role in groundwater recharge across North-West India and serve as the origin or catchment area for several important rivers, including the Chambal, Sabarmati and Luni.

Ecologically, the region supports diverse scrub forests and grasslands and is home to over 120 bird species, around 300 native plant species, and mammals such as jackals, mongooses, hyenas and leopards.

An internal assessment by the Forest Survey of India (FSI) highlights the scale of the change brought about by the new definition. Of the 12,081 hills mapped across the Aravalli region, only 1,048, approximately 8.7 pc meet the revised elevation-based criterion. This effectively excludes over 90 pc of landforms that were previously considered part of the Aravalli ecosystem, particularly low-lying hills and degraded ridges that nonetheless perform critical ecological functions.

Environmental experts have expressed concern that the revised definition could significantly reduce the scope of legal protection available to the Aravallis, especially in urbanising districts such as Gurugram, Faridabad and Nuh in Haryana.

In these areas, the terrain often consists of fragmented or low-elevation hill systems that may not meet the 100 m threshold but remain vital for biodiversity, climate regulation and groundwater recharge.

Critics argue that focussing solely on elevation overlooks the living ecological systems that characterise the Aravallis. These include scrub forests, wildlife corridors and recharge zones that sustain water tables in some of India’s most water-stressed regions.

Conservationists have also pointed out that the ecological importance of the Aravallis lies not merely in the age of their rocks, estimated by geologists to be over a billion years old, but in their ongoing environmental services.

Bhavreen Kandhari, an environmentalist says that the judgement by the SC will have an impact on the wildlife habitats and corridors used by leopards and birds. It will also disrupt a fragile and highly eroded mountain.

“The new judgement will remove the safeguards from the low elevation hills that are crucial for ecological continuity, groundwater recharge and landscape connectivity. By exempting these lower formations from earlier restrictions, the judgement risks accelerating mining, real estate development, and illegal extraction, even though new leases are temporarily paused. Ecologically, the exclusion fragments wildlife habitats and corridors used by species such as leopards and birds, disrupting an already fragile and highly eroded mountain system,” Kandhari tells Media India Group.

“Also, these rocky structures play a key role in rainwater percolation; its degradation could further exacerbate groundwater scarcity in water stressed regions like Haryana and Rajasthan. The height-based definition ignores the Aravalli’s holistic ecological functions such as slope dynamics, buffer zones and micro climate regulation, by prioritising a narrow, “field-verifiable” metric over ecosystem-based protection,” she adds.

While the revised definition potentially opens up large areas for future development or mining by reclassifying them as non-hills, the court has simultaneously ordered the preparation of a Management Plan for Sustainable Mining (MPSM) to regulate existing mining activities in the region.

Observers note that this dual approach has created ambiguity regarding whether conservation or controlled exploitation is being prioritised.

Concerns about mining are not new. In 2018, a Supreme Court-appointed committee reported that 31 of the 128 identified Aravalli hills had disappeared over the previous five decades due to extensive mining and illegal quarrying. The committee also documented 10 to 12 gaps in the mountain chain, a fragmentation that has been linked to worsening air quality and increased desertification in adjoining areas.

The Supreme Court’s decision has also drawn sharp response from politicians. Former Rajasthan Chief Minister Ashok Gehlot has publicly opposed the revised definition, describing it as a “red carpet” for ecological destruction. He has urged the court to reconsider the judgement, citing the long-term environmental consequences for future generations.

As urban expansion, infrastructure projects and mining pressures continue to intensify across North-West India, the implications of the new Aravalli definition are likely to be closely monitored.

Environmentalists warn that without a landscape-level approach to protection, the remaining fragments of one of India’s most ancient mountain systems could face accelerated degradation.