Reelpolitik

India & You

May-June 2019

The last two years have seen a spate of Hindi films based on key political personalities as well as political incidents in the history of independent India. Quite a few seem to toe the line propagated by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, whose charisma is translating itself into cinematic narratives of hyper-nationalism and toxic masculinity. Is it good business for cine producers or simply another propaganda tool.

Elected in 2014, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi, seeking his second term to office, has over 42 million followers on Facebook, the highest for any politician in the world. He also boasts of 37 million followers on Twitter.

Master of the medium and a combative communicator, his behind-the-scenes images and intrepid thoughts are lapped up by his die-hard supporters. Modi is “India’s first social media Prime Minister,” wrote British daily, Financial Times.

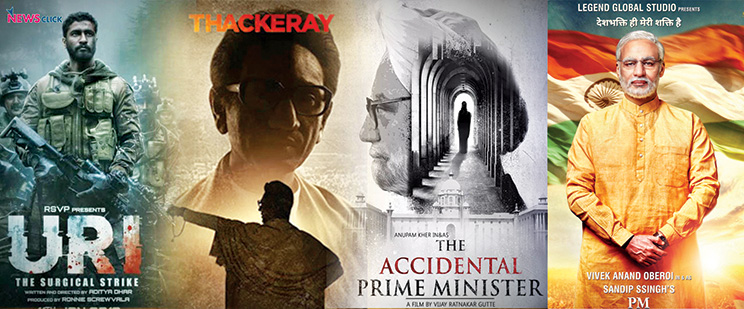

He continues to hit the headlines both in the print and ratings-hungry television news channels that seem to operate under self-censorship of sorts, never crossing the ‘party line’ or asking any hard questions. The glowing media coverage has bolstered his image and improved his popularity, despite many unpopular decisions. And over the last couple of years, this effort has been aided by Hindi cinema as a number of mainstream films, taking up controversial historical issues and examining them from the ruling party’s perspective or simply films on Modi’s pet themes and initiatives. To crown it all, in early April, a biopic on Narendra Modi, directed by Omung Kumar, featuring Vivek Oberoi was set to be released, just in time for the general elections that Modi is trying to win in order to keep the top job.

After dilly-dallying for a long while as the film’s timing was suspicious, the Election Commission of India (EC) banned the release of the film, making the producers approach the Supreme Court of India, which, however, refused to intervene.

The banned film showcases Modi as a leader with remarkable courage, wisdom, patience, dedication to his people, as well as promotes him as a political genius with rare leadership qualities that inspired a thousand social changes, first in Gujarat and then across India.

It traces his childhood in the 1950s to his meteoric rise in the corridors of politics, as a four-time Chief Minister of Gujarat. The biopic culminates in the Prime Minister overcoming all obstacles to create and lead one of the most fascinating and successful election campaigns in the world in 2013-14, to finally become India’s supreme leader.

Political biopics galore

The biopic on Prime Minister Modi is not the only one to have run afoul of the poll body’s Code of Conduct that is in force till the end of the election on May 23. Baghini (The Tigress), a film by Nehal Dutta, profiling West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee, has also been banned and the EC ordered the removal of the film’s trailer from at least three websites.

However, not all politically-inspired films or biopics of other politicians have faced the poll body’s crackdown. One profiled Bal Keshav Thackeray, founder of Shiv Sena, an extreme right-wing regional party in Maharashtra. The film, featuring Nawazuddin Siddiqui in the lead role, was released in January this year. Not all biopics have been glowing as Modi’s or Thackeray’s. In January, as the country was just getting ready for the election, The Accidental Prime Minister was released. The film was based on an eponymous and controversial book with the same name, on the former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh by his erstwhile media advisor Sanjaya Baru, which mocked the Nehru-Gandhi family and the former Prime Minister, and raked in INR 310 million (USD 4.5 million)

South India, for decades dominated by cinematic heavyweights, too contributed to the new wave of biopics. The Telugu Desam Party, the ruling party in the southern state of Andhra Pradesh, has started with a two-part biopic of party founder, actor-turned-politician NT Rama Rao.

The first part, NTR: Kathanayakudu, which hit the screens early January featuring NTR’s fourth son Balakrishna, along with actress Vidya Balan, drew a lukewarm response on the box office. Mahi V Raghav’s YS Rajashekhara Reddy biopic Yatra starring famous star Mammootty in the lead role hit the screens in February. It was based on Andhra Pradesh’s late Chief Minister, YSR, who had embarked on a 1,500 km walking tour, interacting with his followers as part of his election campaign that helped catapult the Congress to power in undivided Andhra.

Good business

If biopics helped push political agendas, other films boosted patriotic flag-waving jingoism, the staple diet for the brand of politics pursued by the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party.

In his directorial debut, Aditya Dhar made Uri-The Surgical Strike that depicted the dramatised account of a covert operation by the Indian army special forces, avenging the killing of fellow army men at their base by a terrorist group.

The love-thy-army and nation storyline, shot on a budget of INR 280 million (USD 4 million), in Serbia with extensive assistance from former Yugoslav military, has raked INR 3.36 billion (USD 50 million) since its release in January.

Similarly, Toilet: Ek Prem Katha, inspired by Modi’s Swachh Bharat Abhiyan (Clean India Campaign) spoke of the problem of open defecation. In the process, it raked USD 49 million in 2017. Released in September 2018 was Sui Dhaga (Needle and Thread), also inspired by Prime Minister Modi’s flagship programme, Make in India, that failed to take off. This movie, too, did well, raking in INR 1,250 million (USD 18 million).

Killing two birds with a stone

Clearly, for some of the ‘politically-inspired’ films, it turned out to be a wise bet for the producers as not only did they please the audiences and raked in big profits, but they also pleased the political masters at whom the films were really directed.

As a ruling class privilege, propaganda films present a sanitised version of the truth and create a feel-good factor for the perpetuation of political power. Any art and creativity in this are incidental. A German woman, Leni Riefenstahl, was one of the greatest film publicists of all times whose talents led her to create some of the best propaganda feature-length films praising the Nazi Party under Hitler. She is best known today for two of her works, The Triumph of Will and the Berlin Olympics of 1936.

Chandigarh-based award-winning theatre personality, Neelam Mansingh Chowdhry, points out that biopics are merely propaganda films, with highly appropriate timings. “These are specifically agenda-driven. They definitely influence the masses and reassert the narrative, which the public has been served for the past five years,” she asserts, adding that there have been good biopics made in the past as well. (See Box) Sandeep Singh has worn several hats – as a producer, creative director, singer and one who came up with the story for the movie on Prime Minister Narendra Modi, has also made biopics on Mary Kom, an International, female boxer, and on Sarabjit, an alleged Indian spy who was killed in a Pakistan jail.

“Cinema is the biggest messenger with the widest reach,” Singh admits on the issue of biopics being political tools. The tagline of the film on Modi says it all. Deshbhakti hi meri shakti hai, (Patriotism is my Strength), proof enough that the biopic is nothing, but a hagiography.

Observes Avinash Das, writer and director of Anarkali of Arrah, (a film that portrays the pangs and helplessness of the dancing community in north India): “Even though I’m yet to watch the movie, my feedback after watching its trailer is not good,” he says, adding that “It raises question marks on the authenticity of the film.”

Noted film historian S Theodore Baskaran strongly believes that biopics cannot be called political films. “They are often made for a political purpose. Usually, there are highly sanitised versions” he points, adding, “I do not think they influence the voters.” (See Interview Box)

Political, but not propaganda

Making political films is not something new in India, a country where the masses, even the illiterate or poor, are enamoured with politics and discuss it threadbare almost every day as do the hundreds of television news channels and tens of thousands of newspapers. Hence, film producers in various languages have been making political films for decades. However, unlike the current crop of propaganda biopics, several political films have been made which have sharply criticised the political establishment, as well as the ruling party and the upper classes. Sudhir Mishra’s Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi (A Thousand Wishes Like This) was a political drama seeking to reinterpret the deadly days of left-wing activism in Indian campuses during the 1960s and 1970s and the subsequent disillusionment.

Kissa Kursi Ka (A Story of the Throne), made by the then Member of Parliament and little-known filmmaker Amrit Nahata in 1975, was a political satire on Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s son Sanjay Gandhi and his acolytes’ mercurial approach in conducting affairs of the party and the government. The film was however banned soon after when a state of emergency had been declared in the country and all the prints of the film seized. Sandesham (The Message) directed by Sathyan Anthikkad in 1991 in Malayalam, is a political satire on contemporary Kerala politics where brothers turn local leaders of rival parties, leading to distress for their aged and once-proud parents.

Moreover, political themes have always found expression in the works of Indian filmmakers such as Shyam Benegal, Govind Nihalani, Mrinal Sen and Goutam Ghose. Benegal’s Nishant (1975), marking Naseeruddin Shah’s debut, Ghose’s Paar (1984) and Nihalani’s Ardh Satya (1983), caught public imagination in those times.

Movies in India, commercial or parallel cinema, propaganda films and political biopics, are not only a great source of entertainment, but also a parallel vehicle of information, education, and communication.

The Indian political class is searching for a place of its own in this uncharted territory. If it helps in any way in the resurrection or perpetuation of a leader’s image and political party’s fortune, it will go for this whole hog. What’s more, this is just the beginning.

Biopics are not political films

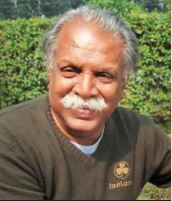

S THEODORE BASKARAN, Film Books Writer

S Theodore Baskaran, noted film historian, has written several books on the film and entertainment industry in India

Several biopics are hitting the market at the time of elections. Can they be called political films or just hagiography at the best?

A French director said, “Political films are different from films that are made politically.” In other words, in political films, the ideology will run through the film, in the story, in the visual, not by preaching. You have to be an expert filmmaker to make political films.

Which, according to you, have been the best political films made in India across languages?

A few directors like Mrinal Sen and Govind Nihlani did. And a few others. Adoor Gopalakrishnan’s Mukhamukham (Face to Face) is a good example of a political film. Similarly, Kabani Nadi’s Chuvannappol (When the River Kabini Turned Red) by P A Backer in Malayalam is a good example. So is Agraharathil Oru Kazhuthai (Donkey in a Brahmin Ghetto) by John Abraham in Tamil.

How far these biopics can colonise the minds of the audience and turn them voters for a particular party?

Biopics cannot be called political films. But, they are often made for a political purpose. Our biopics are in the usual entertainment format. Nothing different. Usually, there are highly sanitised versions. I do not think they influence the voters. There is a close connection between cinema and politics in South India especially Tamil Nadu. Using films for propagating ideology, the DMK sought to capitalise on star popularity as a vehicle for political mobilisation.

In Tamil Nadu, stars used their popularity and rode piggyback on it into politics. Their Cinema was not used to propagate ideology.

Do you see the emergence of saffron cinema? Or is it mere propaganda- a fad that will fade away?

I do not see the emergence of saffron cinema.

Do documentary makers in India make better political documentaries compared to filmmakers making political cinema?

There are very good documentary filmmakers whose work is very political, like Anand Patwardhan or Deepa Dhanaraj. You cannot compare two different kinds of cinema.

Parasakthi (The Goddess, 1952) is considered one of the most controversial films of Tamil cinema and also has the one that is considered the most controversial scene. It was also a major tool in propagating the ideology of the DMK party. What is your take?

I do not agree with your statements on Parasakthi. It was not produced by any DMK leader. Only the dialogue, not even the story was written by Karunanidhi. It had general radical rhetoric, anti-religious, anti-priest hook ideas. It did not spread DMK ideology. What you mention is the popular take on that film.