Death by breath in Delhi: Irate residents complain of inaction over air pollution

Poor, homeless worst hit as winter smog seeps into daily lives

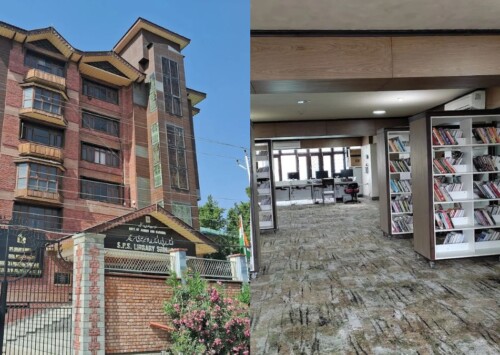

With AQI levels breaching the hazardous 500 mark, breathing in Delhi has become a health hazard (Photos: Media India Group/Aman Kanojiya)

For past several weeks, the Indian capital has been fighting for every breath as a dense layer hazardous air has covered the entire capital and its surroundings. Residents across diverse age groups and social classes struggle with failing health, disrupted livelihoods and shrinking mobility. From night shelters to affluent neighbourhoods, toxic pollution has turned breathing into a daily challenge. Voices from the ground reveal how inaction continues to cost Delhi its air, health and dignity and though the affluent can seek momentary solace with their air purifiers, the homeless and the large number of poor have no way to escape the gas chamber that the city has become.

With AQI levels breaching the hazardous 500 mark, breathing in Delhi has become a health hazard (Photos: Media India Group/Aman Kanojiya)

Every winter, a thick blanket of smog descends over India’s capital, but this year the impact has been far deeper and more relentless. For well over a month, now, polluted air has disrupted health, livelihoods and mobility, forcing citizens, from night shelters and middle-class neighbourhoods to affluent colonies, indoors and overwhelming healthcare systems.

For many Delhiites, pollution is no longer a seasonal inconvenience, but a persistent public health crisis that refuses to ease.

“I struggle to breathe every single day. My chest feels heavy, as if air is not going inside at all,” Salim Mohammad, a 45-year-old catering worker who lives in a night shelter at Chandni Chowk in Old Delhi, tells Media India Group.

Salim says that his condition worsens at night. “Even while sleeping, my breath starts swelling and I feel suffocated. Sometimes it becomes so bad that I feel dizzy and almost lose consciousness. I cannot spend even a single day without my inhaler. This pollution is stealing my breath,” he adds.

According to him, Delhi’s air has deteriorated sharply over the years. “Earlier there was some discomfort, but nothing like this. Now my eyes burn constantly and even stepping outside feels difficult. The air is no longer normal, it makes people sick,” says Salim.

Living in a night shelter has made matters worse. “For poor people, there is neither proper free treatment nor clean air. People in night shelters are already vulnerable. If the system was really working, I would not be surviving my life dependent on an inhaler,” he remarks.

The health crisis has directly impacted his livelihood. “I work in catering, but for the last one to one-and-a-half months, I have not been able to go to work. If I stand for a short time, my breath starts swelling. Carrying utensils or even walking becomes difficult. When I cannot work, my income stops. Pollution has taken away not just my health, but also my livelihood,” adds Salim.

The impact of toxic air is not limited to those on the margins. Twenty-eight-year-old Vanshika Garg, a resident of Adarsh Nagar, in northern Delhi, says pollution has seeped into daily life and lungs alike.

“I am facing serious breathing issues. It starts with cough and throat irritation, and then its effect spreads across the entire body. Performing daily activities has become difficult. Overall, my health has taken a severe hit,” she tells Media India Group.

“It feels like all pollution particles have entered our lungs. Even if we don’t want to, we are inhaling smoke every day,” she adds.

Garg points out that air quality has been worsening every year. “This year is much worse. There is constant burning in the eyes, throat irritation and uneasiness. Visibility has dropped so much that travelling feels unsafe, especially in the mornings,” she says.

According to her, the most vulnerable sections are paying the highest price. “Asthmatic patients, elderly people and those above 40 are facing severe problems. Many are forced to stay confined indoors. When breathing itself becomes difficult, how does one step out to work?” she asks.

She believes that government action remains inadequate. “Pollution is predictable every year from October, yet there is no timely preparation. This year, even the ban on firecrackers was lifted. There is no clarity on stubble burning or AQI control. December has already arrived, but no serious preventive measures are visible,” Garg says.

For those whose jobs require outdoor work, the situation is even more alarming. “Daily wage labourers and unorganised workers do not have the option to stay indoors. Advisories say ‘stay at home’, but if they don’t work, they don’t earn. If they work, their health deteriorates,” she adds.

Twenty-seven-year-old Prerna Saurot from Chhatarpur Extension in South Delhi, has been unwell for over a month, a condition she attributes directly to pollution.

“People are falling sick continuously. I myself have not recovered for the last one and a half months. Normally, illnesses go away in a few days, but this is a continuous condition. I still have a cough,” Saurot tells Media India Group.

She says that pollution has also affected her eyes severely. “I developed a serious eye infection. After sleeping at night, my eyes would be completely stuck together in the morning. This is my real experience,” she says.

Saurot describes the city’s air as dangerously opaque. “The air quality has become so bad that it is hard to tell the difference between fog and pollution. My father, who lives in Ludhiana, was shocked when he visited Delhi, as nearby buildings were barely visible. I even saw a video from Noida where a woman living on the 20th floor could not see anything below. This is not normal,” she says.

She believes children and elderly people are the worst affected. “Making children wear masks is practically impossible. They end up inhaling the same polluted air. Air purifiers are not a real solution either, not everyone can afford them, and the moment a door opens, polluted air rushes inside. How long can we protect ourselves?” Saurot asks.

The prolonged illness has disrupted her professional life as well. “If a person is not healthy, how will they work? Most of the time goes into doctor visits, medicines and recovery. Meetings get missed, office becomes difficult, productivity drops. Managing health, work and personal life together has become extremely hard,” she adds.

For 67-and-a-half-year-old C Khilnani, who has spent his entire life in Delhi, the transformation of the city’s air is deeply painful.

“I live in Jangpura Extension, one of Delhi’s well-off neighbourhoods, yet the suffering caused by pollution cannot be described in words. My eyes burn constantly, my throat remains irritated and my cough does not stop,” Khilnani tells Media India Group.

When he consulted a doctor, the response left him shaken. “The doctor told me very clearly, living in Delhi means you have to bear the impact of pollution. I was born here, I grew up here, and today I cannot breathe properly in my own city,” Khilnani adds.

He observes a repeating cycle every year. “Pollution keeps increasing. It moves from Grade Four to Grade Three for barely two weeks and then returns to Grade Four. Nobody knows how long this will continue. I never imagined seeing such pollution in my lifetime,” he adds.

Khilnani feels that the government’s priorities lie elsewhere. “The government appears more focussed on elections and politics than on pollution. This is a serious issue that needs continuous and urgent action,” he says.

The impact on daily functioning is severe. “When you cannot step outside, when you have to wear a mask all day, and when your eyes keep burning, how will you focus on work? In these conditions, even living a normal life becomes difficult,” Khilnani remarks.

Across age groups, neighbourhoods and economic backgrounds, Delhi’s residents are united by a common reality, polluted air is damaging health, disrupting livelihoods and shrinking everyday freedom. While advisories urge people to stay indoors, millions have no choice but to step out and breathe toxic air.

As winter deepens and pollution levels remain hazardous, the question remains unanswered: how long will Delhi’s people continue to pay the price for inaction?