Death penalty in India: A questionable debate

The Supreme Court has regularly advised judges of lower courts to apply the extreme punishment only in the ‘rarest of rare cases’

The hanging of four persons convicted for the brutal rape and murder in ‘Nirbhaya’ case in Delhi on Friday brings the issue of death penalty back in focus. Is death sentence a deterrent?

Whenever any heinous crime happens in India the first demand by the people is to hang the accused. To many common persons, capital punishment seems to be the right punishment for a variety of crimes.

The capital punishment of the four convicts- Mukesh Singh (32), Pawan Gupta (25), Vinay Sharma (26) and Akshay Kumar Singh (31) for the 2012 gang rape and murder of the 23-year-old physiotherapy intern, who later came to be known as ‘Nirbhaya’, were hanged at 5.30 am on Friday inside Delhi’s Tihar Jail.

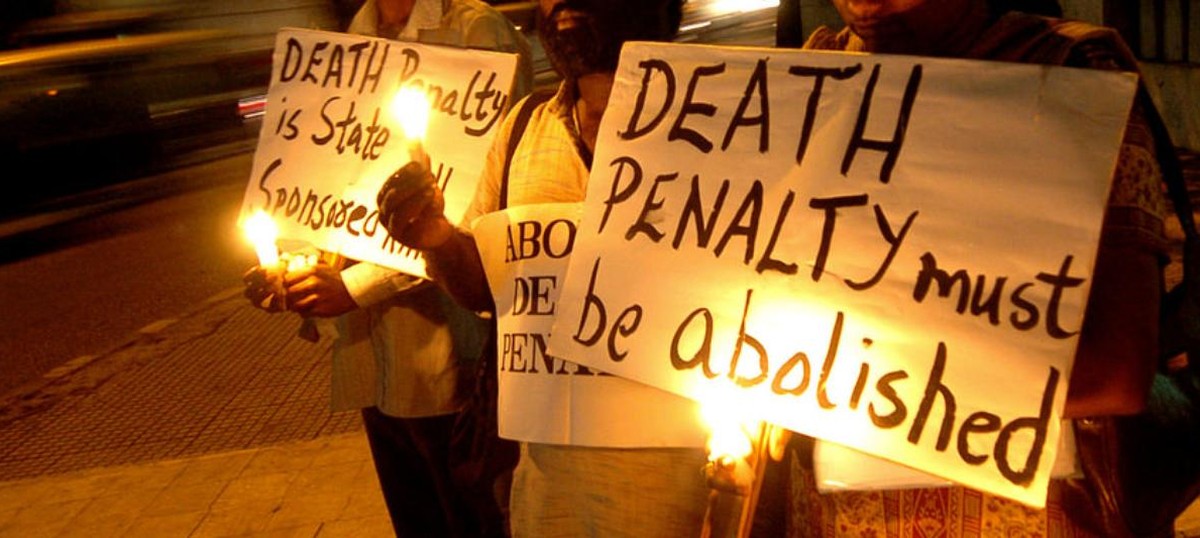

Soon after the execution several organisations criticised the continued application of death penalty in India. The International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) condemned the hanging of the four, stating that the execution of the perpetrators was an “affront to rule of law and does not improve access to justice for women.”

Denouncing the executions, the ICJ urged the Centre to abolish death penalty and introduce “systematic changes” to the legal framework to deter violence and improve access to justice for women.

Similarly, Amnesty International India called the hanging of the four convicts a ‘dark stain’ on India’s human rights record. “Since August 2015, India had not executed anyone and it is unfortunate that four men were executed today in the name of tackling violence against women. All too often lawmakers in India hold up the death penalty as a symbol of their resolve to tackle crime.”

“The death penalty is never the solution and today’s resumption of executions adds another dark stain to India’s human rights record. Indian courts have repeatedly found it to be applied arbitrarily and inconsistently,” said Avinash Kumar, executive director, Amnesty International India.

But there are several proponents for the death penalty also. ‘‘This (Nirbhaya) case was definitely the rarest of the rare and the four deserved the death penalty,’’ Kalyan Bhaumik, advocate, Supreme Court of India, tells Media India Group. Besides the victims parents, thousands of other Indians and several media too ‘celebrated’ the hanging, saying it would deter others from committing heinous crimes.

Will death penalty stop rapes in India?

The answer is a definite no. As per government data, thousands of rapes take place every year with a consistent rise in numbers every year. According to recent figures from the National Crime Records Bureau, police registered 33,977 cases of rape in 2018 – that’s an average of 93 every day. These are the figures of cases that are reported, campaigners say thousands of rapes and cases of sexual assault are not even reported to the police.

Amnesty’s Kumar says that what is actually needed are effective, long-term solutions like prevention and protection mechanisms to reduce gender-based violence, improving investigations, prosecutions and support for victims’ families. “Far-reaching procedural and institutional reforms are the need of the hour,” he added.

The opposition to capital punishment is not limited to the well-educated or liberal classes in the country. Even several common persons also believe that capital punishment is unjust and should be abolished. ‘‘All the time, it is the poor and the helpless who are hanged to death. How come in our country, the rich and well-connected always escape punishment, let alone death punishment. And since death is the ultimate punishment, it should not be applied in any case,’’ Awadesh Sahu, a 29-year-old mason in Mumbai who hails from Madhubani, in Bihar, tells Media India Group.

Abolishing death

Sahu and Amnesty are not the only advocating abolition of capital punishment. In August 2015, the Law Commission of India, which frames policy recommendations to the government of India, called for abolition of death penalty in India, citing the example of 140 other nations in the world where capital punishment has been banned as well as numerous resolutions adopted by the United Nations General Assembly asking for all nations in the world to abolish death penalty.

The Supreme Court of India has been clear in its view on death penalty. It has regularly advised judges of lower courts to apply the extreme punishment only in the ‘rarest of rare cases’. Yet, this direction has been cast aside by most judges of the trial courts. According to the National Law University, New Delhi, in the period 2000-2014, a total of 1,810 persons had been sentenced to death by the trial courts, but the ultimate punishment was confirmed by the Supreme Court only in 73 cases. Incidentally, 443 persons sentenced to death by the lower courts were acquitted by the higher courts.

Yet, the lower courts continue their charge for death penalty. In 2018, they sentenced 162 persons to death, the highest in two decades. As has been the case in the past, most of these sentences are likely to be overturned by the higher courts. Over the decades since independence, the SC has become increasingly reluctant to confirm death penalty in most cases. This reflects in the sharp decline in the number of executions carried out in the country. While India is believed to have carried out nearly 750 executions in seven decades since independence, in the last decade, it has executed seven persons only, including the four hung earlier this week in the ‘Nirbhaya’ case.

Opponents of death penalty in India also cite the rather high number of instances of judicial miscarriage where courts have ended up acquitting persons accused of trumped up charges including terrorism. But the liberty has often come years, if not decades later. But not every time. In a judgment in December 2018, the Delhi High Court acquitted a man who had been sentenced to 10 years in jail for allegedly raping his minor daughter. The HC was highly critical of the trial court judge for ignoring the serious deficiencies in the prosecution case and not taking into account the defence plea for a DNA test. Unfortunately, in this case, too, justice was done too late as the man had died in prison 10 months earlier.

In another case, 11 men, all Muslims, were acquitted by a court 25 years after they were charged with terrorism. The judge of the special terror court hearing the case acquitted them for lack of evidence. In another case, five men, all Muslims again, were acquitted of terror charges by a court 23 years after they were charged and jailed. Opponents of death penalty say there are scores of such cases of wrongful prosecution or framed up charges in the country and most of them involve accused from minorities or socially disadvantaged communities. They say while in these cases the accused were alive and hence could yet have hope, in the case of an innocent person’s execution, there is no recourse for the family. They point at cases where the prosecution’s evidence has been very thin and the only reason for execution being carried out, as was the case of Mohammad Afzal, a Kashmiri professor, who was accused and convicted of being the key conspirator in the December 2001 terror attack on the Indian Parliament that led to 13 deaths.

Soon after his execution, Anjali Mody, who covered the case for The Hindu newspaper wrote, ‘‘There were no witnesses against Mohammed Afzal. Those said to be his co-conspirators were acquitted (Geelani, Shaukat and Afsan), died (Mohammed) or vanished (Tariq). The only other evidence against him are telephone instruments and SIM cards that the police claim to have recovered from him at the time of his arrest, different depending on which police jurisdiction was involved. Besides, one SIM card had been in use before it was sold to him. How different courts interpreted this makes fascinating reading and raises questions about why the case for Afzal Guru’s death was pursued with so much zeal.’’

The Afzal case was back in focus a few weeks ago when Davinder Singh, a senior police officer, was arrested on charges of trying to ‘smuggle’ two alleged terrorists from Kashmir to New Delhi. Incidentally, Singh was a key investigator in the Afzal case and he acknowledged having made Afzal give a ‘confession’, which was thrown out by the Supreme Court as the police had not followed due procedure!