Lessons for EU from India-UK Free Trade Agreement

Deal exposes structural challenges within European Union

The Free Trade Agreement reached between India and the United Kingdom last week is crucial not just for the two signatory countries, but also has important lessons for the European Union which has struggled to reach agreement on FTA with India for the past 13 years.

The India-UK Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) signed on July 24 is a milestone in the India-Britain strategic trade and economic relations. This historic agreement between the world’s fourth and fifth largest economies respectively, represents one of the most economically significant bilateral trade deals in recent times.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi described the agreement as ‘historic’, whilst Keir Starmer, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, emphasised that it marks ‘a new era for trade and the economy’. The free trade agreement encompasses extensive provisions across goods, services, and technology sectors, promising to catalyse trade, investment, growth, job creation, and innovation in both economies.

This represents the largest trade deal the UK has negotiated since Brexit and India’s biggest agreement with a G7 economy in over a decade. It also represents the latest step by the UK and India to strengthen their relationship, building on the Technology Security Initiative, and the UK-India Comprehensive Strategic Partnership, which centres the relationship on mutual economic growth, technological innovation, and collaboration on global challenges including climate change.

From partnership to agreement

The CETA is a culmination of discussions that started after the Enhanced Trade Partnership (ETP) on May 4, 2021, between two governments. This alliance was the bedrock of a solid economic partnership which in fact plotted a course to an CETA and obliged the two countries to double bilateral trade by the year 2030. The agreement builds on an already strong economic relationship, with potential to double trade from USD 56 billion by 2030.

This agreement was expected to be signed before Diwali 2023 but political developments in the UK deprived the then British government under the Conservative Party to ink it. Though negotiations continued, the pace of discussions accelerated following a meeting between Modi and Starmer at the G-20 Summit in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, in November 2024.

When the UK-India negotiations started under the Conservatives, many said it would never be done and therefore this agreement defies many expectations. At the beginning, the negotiations were like a long game of cricket “Test Series” with plenty of sticky wickets along the way but both countries decided that to win a “cricket match negotiations”, it was important to play instead on a T20 format with decisive results and the outcome is evident.

Indeed, this is one of the swiftest FTAs that India has ever reached, considering that talks on EU-India FTA have floundered for almost two decades and even India-ASEAN FTA took almost eight years to reach a common ground.

Despite the pace at which India and the UK worked to reach an agreement, the FTA is unlikely to lead to immediate gains for both the countries with more than half of all tariff reductions delayed beyond 2030. The two nations have also set a 36-month deadline for mutual recognition of professional qualifications to facilitate the movement of professionals like nurses, accountants, and architects to Britain within 36 months.

Challenges for India

The agreement exposes the structural weakness and trade negotiating mechanism of the European Union. The fact that it took only three years and 14 rounds of negotiations for UK to finalise the deal with India, speaks of EU’s complicated and confused trade policy accompanied by directionless negotiating mechanism.

Trade deal between the United States and Japan announced last week and US-EU trade deal announced on July 27 may have added to the urgency for New Delhi to seal trade deal with the US and more so due to the tariffs of 25 pc, besides a ‘penalty’ that US President Donald Trump has imposed on India on July 31.

But despite the additional tariffs, the two sides are working behind the scenes and away from the media glare to reach an agreement and the US trade delegation is likely to visit New Delhi early August to finalise the deal. Having secured an agreement with Britain, India is also testing strategic autonomy in a fractured global trade order. In negotiations with the US, India remains cautious and defensive risking the brunt of punitive tariffs if longstanding disputes are not resolved. Without deeper domestic reform in the country and clearer global alignment in the long term, India’s partial trade opening may not be enough to boost growth or secure its place in the region as a credible rule-maker.

At the same time India, appears to be weighing all options with long term economic, strategic and geo-politics interest of the country in view. As it tries to close multiple trade deals in a highly uncertain global environment, India must also focus on agreements that can help enhance its share in global value chains and manage domestic opposition to opening of sensitive sectors.

A holistic approach to trade negotiations will help India to play a bigger role in the global economy. India potentially offers an alternative in reorganising global supply chains amid growing US–China decoupling, which also gives India a greater leverage in achieving a mutually beneficial outcome in trade discussions.

The trade agreement between India and the UK has set a tone to all the Western powers that New Delhi is ready to trade on its own terms. This diversification gives India leverage, both at the negotiating table and in navigating global economic shocks. If the US imposes higher tariffs or ties trade to more difficult concessions, India could accelerate deals elsewhere, thereby softening the blow.

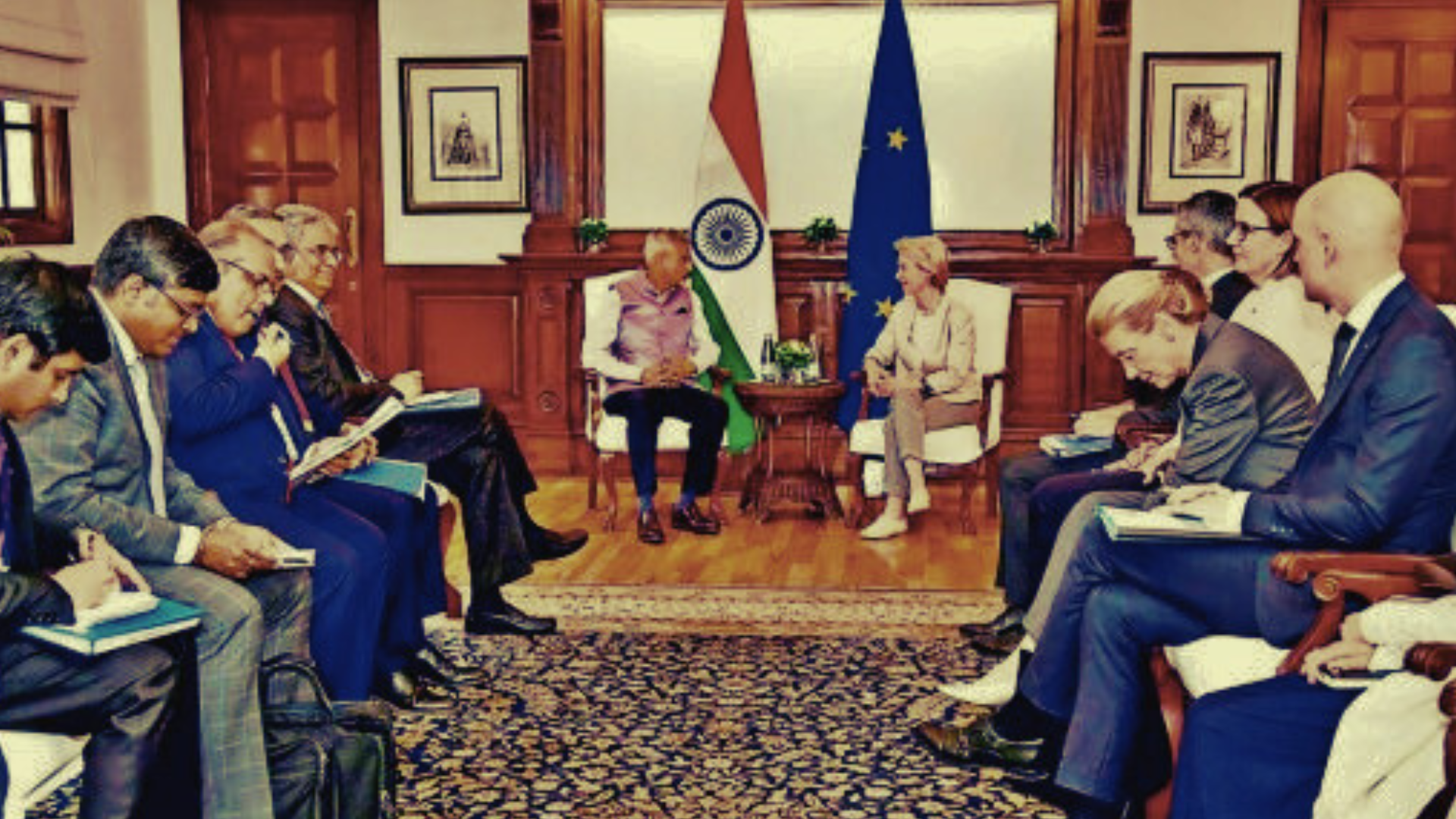

EU-India deal: Despite optimism, negotiations may have stalled

After the successful completion of the India-UK free trade agreement, EU is going to be under pressure to conclude the negotiation with India. India and the EU are preparing for the next round of FTA negotiations in September in New Delhi, following the 12th round of talks in Brussels. Key discussion topics in Brussels included services and market access. Both sides have exchanged their market access offers for goods and services. Some parts of the deal, known as ‘chapters’, have been finalised, while discussions continue on the issues where both sides differ. Both parties aim to finalise the agreement by year-end before the EU-India Summit in New Delhi, potentially increasing India‘s competitiveness in EU markets. The deal with UK may now become a “floor” while offering clarity about the concessions India can make to EU.

If the pact is concluded successfully, Indian goods exports to the EU, such as ready-made garments, pharmaceuticals, steel, petroleum products and electrical machinery, will become more competitive and attractive. The EU is India’s second-largest trading partner, accounting for trade in goods worth EUR 120 billion in 2024, or 11.5 pc of India’s total trade. India is the EU’s 9th largest trading partner, accounting for 2.4 pc of the EU’s total trade in goods in 2024, well behind the USA, with 17.3 pc, China at 14.6 pc or the UK at 10.1 pc. Trade in goods between the EU and India has increased by almost 90 pc in the last decade. The EU market accounts for about 17 pc of India’s total exports, while the EU’s exports to India make up 9 pc of its total overseas shipments.

Despite significant differences in the status of their economic development, it is fair to say that the European Union (EU) and India are often considered “middle powers” by geopolitical pundits. This is admittedly less fair to the EU than it is to India. By the same token, it is argued by many that the EU and India have the potential to occupy independent poles in an emerging multipolar world.

The fact that they are not yet poles is due to interesting and varying reasons. While the EU is incontestably an economic giant, it lacks commensurate geopolitical influence. As for India, while it may find itself in a geopolitical sweet spot, it has miles to go before acquiring serious economic heft. Notwithstanding, this there is a significant amount of strategic convergence between the EU and India.

Unexpected tension and distrust

The EU-India negotiations are also potentially vulnerable to external issues like the EU sanctions on an Indian refinery company Nayara, linked to Russia’s Rosneft, which could create tensions and complicating the negotiation process. On July 18, the EU banned imports of refined products made from Russian crude oil, revised its oil price cap mechanism, and blacklisted over 100 shadow fleet tankers. The council lowered the crude oil price cap from USD 60/barrel to USD 47.60/b, effective September 3. The sanctions, aimed at restricting Russian oil imports and refining, directly affect the Indian refinery company Nayara that relies on Russian crude, potentially disrupting supply chains and raising concerns about energy security and economic sovereignty for India. The sanction has the potentials to introduce a layer of distrust and tension between the EU and India, making it more challenging to reach a mutually beneficial FTA agreement. The EU sanctions has also exposed the height of Western hypocrisy while still importing Russian energy.

The sanctions highlight a divergence in interests, as India is seeking to balance its energy needs with its strategic partnership with Russia, while the EU is prioritising a united front against Russia’s actions in Ukraine. Further, India may view the sanctions as infringing on its economic sovereignty, particularly regarding energy security and the ability to choose its trading partners.

The sanctions could become a major sticking point in the FTA negotiations, potentially stalling or derailing the talks altogether. The EU envoy to India has stated that the EU’s sanctions on Russia aim to weaken its war economy while maintaining global oil market stability. This followed India’s swift and bold response to the decision, in which New Delhi stated that it does not subscribe to any unilateral sanctions measures while emphasising the importance of avoiding double standards, especially in the domain of energy trade.

What next for the UK-India deal and its strategic importance

Meanwhile, the India-UK deal, which is still a non-binding agreement, will have to be ratified by respective parliament of both countries before it becomes effective. It appears very much that it will sail through the scrutiny and will eventually become a legal agreement. The UK-India free trade agreement is viewed as an example of successful economic diplomacy and is set to reshape global capability centres ecosystem in India, transforming both countries from cost-saving units into innovation and value creation hubs.

By integrating digital trade, professional mobility, regulatory coherence, and R&D cooperation, the FTA can help India leapfrog into the top echelon of global digital services exporters. The FTA has the potential to reshape the ecosystem in India by streamlining regulatory, digital and labour mobility barriers. This becomes especially relevant as British firms increasingly seek strategic R&D partnerships and knowledge-based services from India, beyond cost-efficiency goals.

The India-UK CETA is not just a transaction-focussed trade arrangement, but a strategic adjustment to market relations in the multipolar world. The CETA aligns with the UK’s Global Britain vision, enhancing its influence in the Indo-Pacific and countering China’s economic dominance. India’s global trade ambitions too are very much intertwined with its aim to boost exports to USD 2 trillion by 2030, using the FTAs as a key driver. Further, the CETA complements India’s FTAs with Australia and the UAE, positioning India as a global trade hub. It also aligns with India’s own programme for self-reliance in manufacturing.

But, there are already murmurs in the UK that the agreement is heavily tilted in favour of India and in coming weeks we should expect some nasty comments. Although the agreement has been reached, there is however going to be some sense of uneasiness and discomfort in some quarters in Britain and it should not surprise if some politicians in Britain start saying “Though we welcome the deal, we don’t like the way Prime Minister Modi is running this country!”.

(Sunil Prasad is the Secretary General of Brussels based Europe India Chamber of Commerce. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of Media India Group.)