UK-India FTA: Building bridges beyond Brexit

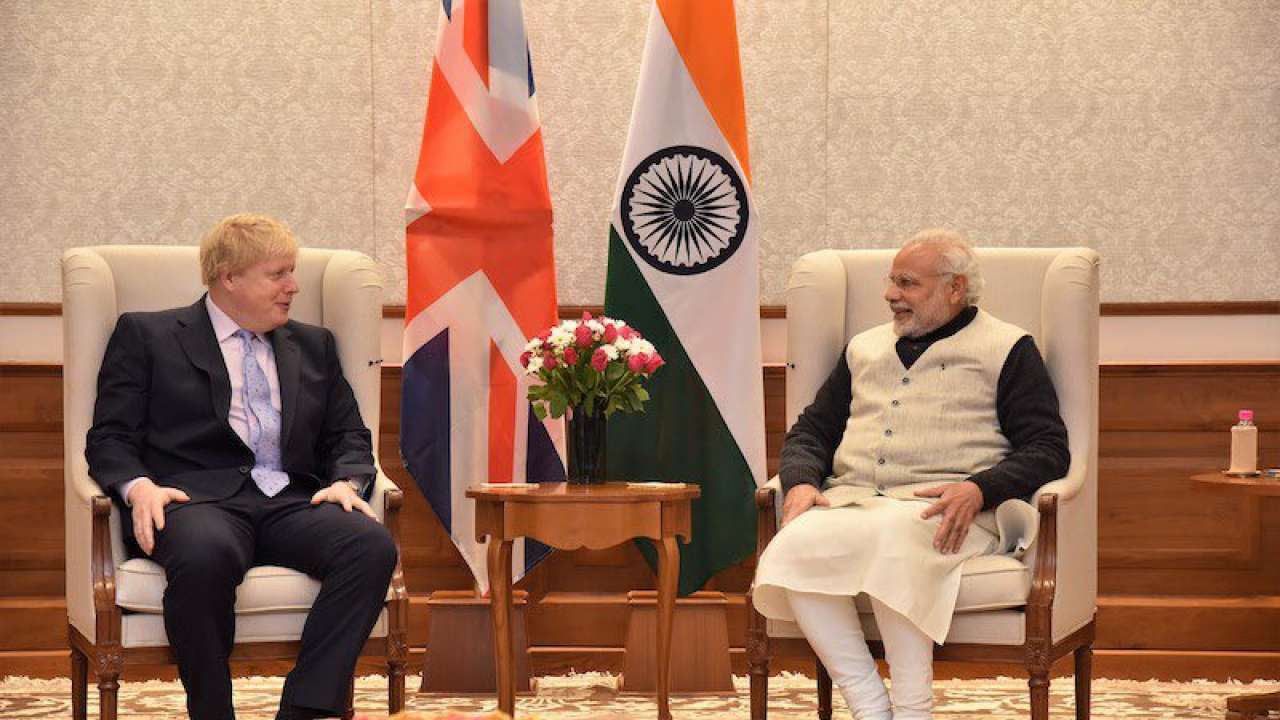

UK and India have committed to work towards doubling their bilateral trade after a virtual meeting between Narendra Modi and Boris Johnson last year

Five years ago, on June 23, 2016, the British people stunned the world by voting yes in the referendum on Brexit. Although the countdown to leave the European Union began in the British summer, Britain had already been working towards establishing direct trade and economic relations with India and major partner countries irrespective of the outcome of the Brexit process.

While Brexit created new opening for the UK to pursue its free trade and economic policies independent of the European Union, it also offered the country a chance to rekindle its trade policies with Commonwealth member states especially with India, Canada, and Australia. Since the Brexit, Europe has changed and so has India, and both have realised that strong economic ties are the bedrock of meaningful strategic relations.

In a virtual meeting on the May 4, 2021, UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson and his Indian counterpart Narendra Modi took a significant step for the future of India-UK relations in signing the 2030 Roadmap for India-UK Relations, which outlines plans for the relationship over the next 10 years. Britain and India want to double trade between their two countries by 2030, up from about USD 31 billion in 2019. Soon after Brexit, the UK has been keen on a free trade agreement with India, but the Indian government was reluctant to go ahead with the discussions as it first wanted to see the terms and conditions of Brexit between the UK and the EU.

When British International Trade Secretary Anne-Marie Trevelyan and Indian Commerce Minister Piyush Goyal met in New Delhi in January to kick off the free trade talks, British Trade Secretary arrived wearing traditional Indian costume Salvaar and Kameez. Perhaps, the message from London was that “We British and Indians have shared past and common future and we are together in the new world order.” The two sides hope to finalise a comprehensive deal within this year.

The first round of negotiations for the bilateral free trade agreement concluded on January 28. The talks covered 26 policy areas including trade in goods and services such as financial services and telecommunications, investment, intellectual property, customs, sanitary and phytosanitary measures, technical barriers to trade, gender, sustainability, and geographical indicators. The negotiations were held virtually for over weeks and saw the coming together of technical experts from both counties for discussions in 32 separate sessions. The second round of negotiations is due to take place on March 7-18.

The Indian negotiating team is led by Nidhi Mani Tripathi, joint secretary, Department of Commerce and the UK negotiating team by a person of Indian origin, Harjinder Kang, director for India Negotiations at the Department for International Trade. This is a perfect negotiating combination with two persons with a shared heritage representing their countries on the table. One must learn from British way of doing things strategically with personal touch with a PIO representing Britain. This also reflects how Indian diaspora have become a part of British life.

The joint statement issued by Goyal and Trevelyan reiterates the targets set by Johnson and Modi last year and states that India-UK bilateral trading relationship is already significant, and both sides have agreed to double their bilateral trade by 2030, as part of Roadmap 2030 announced by the two PMs. The joint statement added that India and the UK sought to reach mutually beneficial agreement supporting jobs, businesses and communities in both countries.

This is the most ambitious round of trade talks that Britain has launched since Brexit. The UK is looking to bolster its trade volumes, which have taken a major hit since leaving the European Union.

In the EU-India FTA context

After four years of frozen discussion, India and EU have restarted negotiations on the FTA. Though the progress is neither significant nor promising, it could be called a “fresh air discussion”. The FTA negotiations between EU and India which started in 2007 is still stuck on difficult issues such India’s intellectual property regime, India’s duty and tariffs in areas of wine, spirits, dairy products and India’s protectionism of its automobile sectors amongst others. India is concerned about EU’s lavish subsidies to its agro-industry, imposition of temporary import restrictions as well as inordinate delay in recognising India as data secure country.

Last year, the UK and the EU separately announced their intention to negotiate a free trade agreement (FTA) with India with fresh energy and new ideas. This was a significant development, not only from an international trade perspective, but also from the perspective of geo-politics. For India, FTAs with the UK and the EU have the potential of integrating it with the dominant global value chain of trade, and for the UK and the EU, FTAs with India would not only provide them an enhanced access to one of the largest and fastest growing markets as well as manufacturing hubs in the world, ensuring supply chain resilience, but would also enhance their economic and political influence in the Indo-Pacific region.

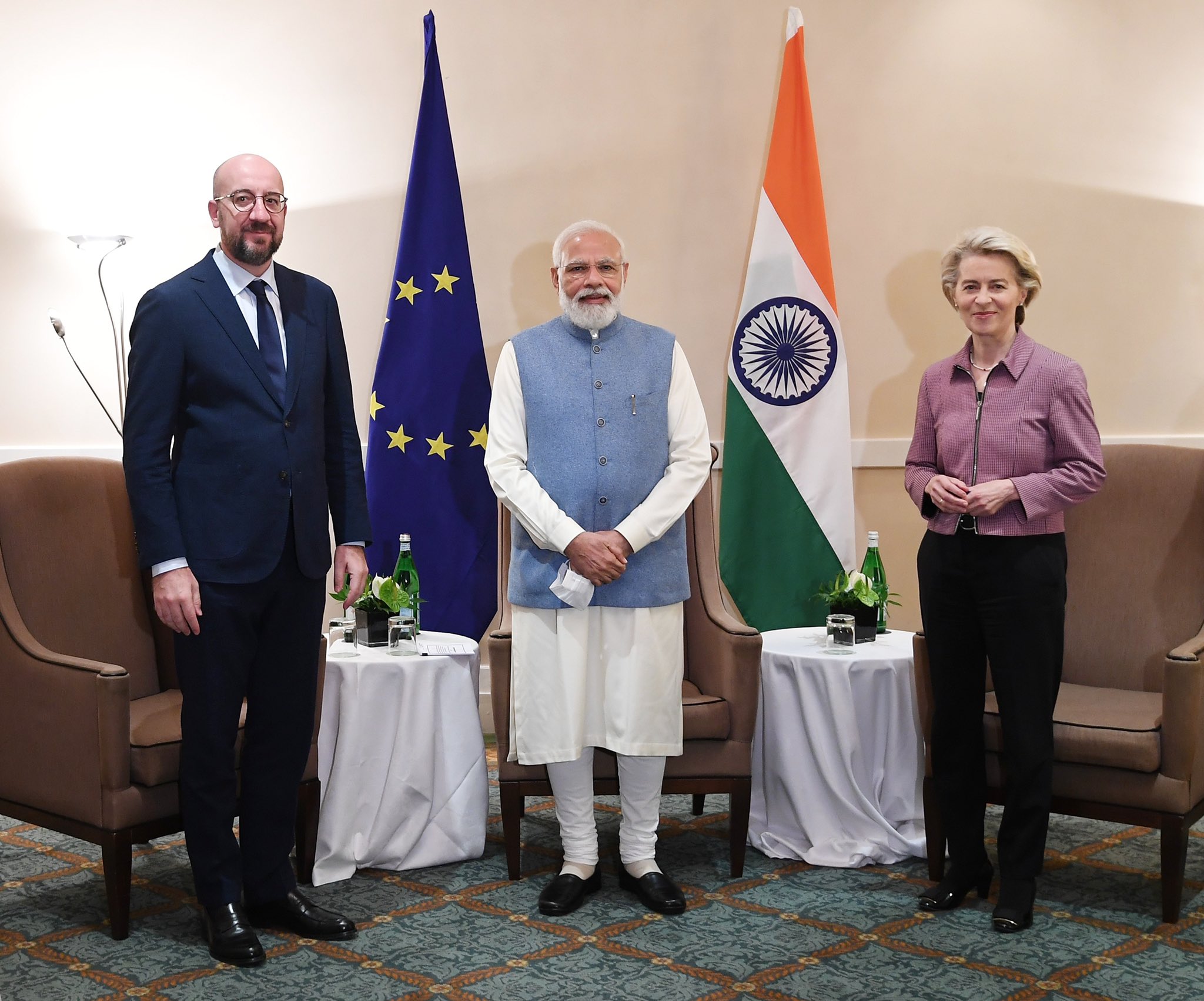

Narendra Modi with Ursula Von der Leyen, President of European Commission and Charles Michel, President of the European Council

Rationale behind FTA

Irrespective of developments in the global economic and political order and new strategic alliances, India and Britain have had a special relationship over the last few years and more particularly in the last seven years under the National Democratic Alliance in India and under Conservatives in Britain. As UK has no unrestricted access to European markets post-Brexit, it was important for the UK to build closer trade relationship with India as it offered an opportunity for UK businesses to not only sell products and services to India’s burgeoning middle class, but also play a major role in tapping business opportunities which is available in the fastest growing economy of the world. There are about 800 Indian companies operating in the UK which together employ more than 100,000 people. The ongoing collaboration between UK and India in developing Covid-19 vaccine highlights the importance of their bilateral relationship.

The British government is desperately wanting to strengthen its economic alliances around the world following the EU divorce. As Brexit has started to show its expected negative impact on the British economy, an ongoing fishing dispute with France not getting resolved, and several logistical and other complications arising out of Brexit still hanging fire, over a year after Britian has walked out, the UK cannot afford to live in isolation of global trade and free trade discussion with India is an attempt to show the EU that UK is not a loser. A free trade deal with India has thus become one of the key priorities for British PM Johnson. This despite the fact EU remains India’s second largest trading partner and the total volume of trade at stake in a UK-India agreement is dwarfed by Britain’s commerce with the EU. In 2019, trade with India was equivalent to about 3 pc of the UK’s total trade with the EU.

Majority Indian companies have used Britain as launching pad for entering the EU market. As Brexit has imposed restrictictions on free movement of goods, services, capital and human resources, Indian companies have had to find places where they can tap the EU market from. This is a setback for the UK which obviously does not want the situation to escalate to level where there is exodus of Indian companies from the UK as if the Indian companies have to opt between the EU and the UK, the choice is a given. The EU is a large market with a population of 500 million people, spread across 27 countries as against the UK’s 65 million.

Outside of trade, a major roadblock in UK-India relationship will be the visa issues related to the movement of people as this is a politically sensitive issue both in the UK and India. The visa issue had recently prompted Indian commerce minister to say that the ‘visa issue sounds like non-tariff barriers in services sector’ and that UK is ‘no longer treating India as an old friend’.

If the FTA with India is signed, it will benefit UK companies through removal of tariffs on high value exports like machinery, metals, pharmaceuticals and whisky amongst others. As for India, the major beneficiary of the FTA will be the apparel and footwear sector as tax and tariffs are impeding the competitiveness of India’s apparel and footwear sector. However, UK-India FTA is not a zero-sum game but “give and take” and mutual understanding, partnership and participation will be the key to a successful negotiation. One also cannot ignore India’s soft power in making UK-India relations lively. Soft power has long been a persuasive approach to international relations, typically involving economic and cultural influence and as nothing runs deeper into a culture than food, “Chicken Tikka Masala”, the national dish of Britain and the USD 2 billion dollar industry will play its role in the FTA talks. It is also important that UK-India relations must also not be seen through the prism of delay in deporting Indian fugitives who have made London their safe heaven but through the challenges that both India and UK face together in the changing world order.

For Britain, FTA with India is not an option but a necessity. Since Brexit, Britain has been desperately seeking to woo its old flame, the Commonwealth, even as its 51 other member states are not exactly sure of what to expect from Britain, what Britain wants, and if Britain is the right partner given rising economic and strategic influence of the EU and the US and changing global order. Most Commonwealth states now are not dependent on Britain but have charted their own economic future with alliances and partnerships. Changing dynamics of global power especially, importance of the dynamic Asia-Pacific region, have all given a new direction to major Commonwealth countries. Britain would therefore find it very hard navigating fresh agreements with dozens of countries and rewriting many laws.

Building bridges post Brexit

The UK-India relationship is time-tested and historic, and Brexit has provided a perfect opportunity to enhance their trade relationship with FTA will be just one of these potential benefits. The key themes that underpin their relationship are trade, investment and finance, technology, security & defence, migration & home affairs and the Living Bridge.

In the post-Brexit European order, Britain is looking for solid international partners to retain its position as global investment destination and also at the top of the global order. As a result, stronger trade and economic ties with India have become a major political priority for London under Boris Johnson’s government. Indeed, Britain’s relations with India have never looked as promising as today but this narrative on bilateral relations remains mired in the past as Delhi can’t shake off the Pakistan prism in viewing London allowing anti-India campaign by Pakistan from its soil.

It is, however, important to state that ambition to conclude a comprehensive UK-India trade agreement in the next few months should be taken with a large pinch of salt given India’s track record of starting negotiations but hardly finishing it on time. India pulling out of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, a club of 15 nations in the Asia-Pacific region that together count for 2.2 billion peole and 30 pc of global economy with collective GDP of USD 29.7 trillion, is also a reminder of India’s unstable free trade policies.

Because of the complexity of the issues involved and the complicated structure of the EU which hampers the trade negotiations rather than helping in solving it, concluding UK-India free trade agreement looks promising. The issues involved in the UK-India trade negotiations are no different from the EU-India trade negotiations but what is different is that here two countries are on the same wavelength but in case of the EU, the agreement goes to several political layers of decision making process and even one “disagreement” can jeopardise the whole agreement, as it happened in the case of EU-Canada FTA when a small province in Belgium Wallonia created very discomforting situation for EU.

One of the reasons for India going slow on EU-India FTA negotiations could be that India first wants to test the ground realities with Britain. An FTA with the UK could be a model on which India could negotiate with EU. We could also say that the fate of the EU-India FTA depends upon the outcome of UK-India FTA negotiations.

Brexit was a “Himalayan Blunder” for which both Britain and all members countries of the EU are responsible. It is true that Brexit freed Britain from the chaos of EU’s endless bureaucratic grinding machine to chart its own course, but one cannot disagree that Britain will have to keep chasing the major trade initiatives EU is taking across the globe so that it is not outshined.

In 2020, theEuropean Union published its new EU-India Strategic Partnership: A Roadmap to 2025 which is no different from UK’s Roadmap to 2030 published last year which paves the way for UK-India FTA. The objectives of the two are so similar that one can get confused as it is apparent that the strategic importance of India for EU and Britain revolves around the same parameters.

Back home in India, the repeal of the three farm laws has weakened Prime Minister Modi’s authority and dented his image as a reformist PM. It was a testing time for Indian democracy as people’s power displayed on the streets prevailed over Parliament. It shows how complicated Indian democracy is and how difficult is to make economic reforms. This is not good news for reform agenda in India as each major economic decision or a major trade agreement will be scrutinised on the streets.

In London, the “Partygate” Scandal has badly bruised PM Johnson and it is difficult to assume his fate. However, Britain’s relations will not be affected even if Johnson has to go, as all major parties in UK are of the strong view to solidify relations with India.

As UK-India trade negotiations advance, the EU will be under increasing pressure to steal the momentum and start negotiating the FTA. Any UK-India FTA will also shake EU’s powerful bureaucracy in Brussels, and they will have to realise that concluding a trade agreement requires vision of today’s realities and tomorrow’s challenges.

-Sunil Prasad is secretary general of the Europe India Chamber of Commerce and lives in Brussels.