Aphantasia: When mind’s eye goes blind

Aphantasia is a neurological condition which makes it either very difficult or completely impossible to visualise (Photo: Positive health online)

Harry Potter fans may remember a scene from Harry potter and the prisoner of Azkaban when Professor Remus Lupin tells Harry to visualise ‘happy memories’ in order to get rid of the dementors? Almost all the people in the world definitely can visualise memories, happy or otherwise, but a few, about 2 -3 pc, cannot visualise their memories at all as they suffer from Aphantasia.

Aphantasia is the inability to form mental images of objects that are not present, or at least that is what Google describes it as, but it is far more complex a condition to be explained away in a few words as most people are not even aware that they may be suffering from it.

“I found out that I had Aphantasia in 2019 after watching a YouTube video created by another illustrator,” says Dan Lynh Pham an illustrator from Oklahoma, USA. “I asked my partner whether or not he could actually visualise images in his mind. That was when I realised that we process information differently. After a lot of discussions, I began to learn more about how visual thinkers experience the world and how my experience diverged from that,” adds Pham.

Described as having a ‘blind mind’s eye’, the phenomena did not even have a formal name as a medical condition until 2015 when Aphantasia was coined by Neurologist Adam Zeman. Yet, it is anything but a new condition. The first reported case of people having a ‘blind mind’s eye’ was way back in 1800s when British phycologist Francis Galton conducted a study with 100 subjects, and told them to visualise a breakfast table, 12 participants reported having either a very dim image in their minds or none at all.

“When someone with Aphantasia does try to visualise something, they simply can’t and instead see blurred images or even a void of darkness,” says neuroscientist Tara Swart, a Senior Lecturer at MIT Sloan. “Aphantasia is complex, and its effect on people can vary. For example, it can manifest itself as the inability to recognize faces, form visual memories, or imagine something new that you haven’t seen before. Though it has no bearing on intelligence or any other neurological syndrome,” she adds.

Thus, little wonder that many of the people who are Aphantasiac realise quite late in life that they have a unique condition. “I found out about Aphantasia in summer 2020 when I stumbled across a YouTube video about it,” says 35-year-old Joel Lux, from Northern Ireland, “as soon as I learned what Aphantasia was, I recognised it as applying to me.”

The video that made Lux and several other Aphantasiacs aware about their condition, is I have Aphantasia (and you may too…without realising it) on YouTube, posted by AmyRightMeow and viewed over five million times. It was one of the very first videos about this topic, which eventually paved the way for many more creators to express their journey being an Aphantasiac artist and how they’ve dealt with it.

Aphantasia is a neurological condition which makes it either very difficult or completely impossible to visualise (Photo: Positive health online)

“Being aware of Aphantasia put many of my experiences into perspective,” says Lux, “As children, my best friends loved to draw. We would spend a lot of time sitting around the table creating monsters, spaceships, drawing comics, and so on. However, their art steadily improved and reflected their perceptions, while mine always remained more abstract or unusual. They were learning to draw realistic people, while mine were always cartoony and non-symmetrical. They would have strong ideas of anatomy or of the design of something they wanted to create, whereas I couldn’t visualise any of it to even begin to recreate it on the page. While their art steadily improved, mine became increasingly abstract. Learning about Aphantasia helped me understand why I couldn’t visualise in the same way they could,” adds Lux.

Another example given by Lux is that whenever he would go to the dentist, he was asked to visualise a pleasant scenario during his procedures, like a calm day on a beach or Disneyland, to distract from the pain but alas! he couldn’t begin to picture it. Others would often talk about how helpful this method was and how much they appreciated it. It got to a point where Lux was annoyed whenever the dentists would try these tricks, he couldn’t understand why he had such a different experience than everyone else, “now it all makes sense,” informs Lux

There are a lot of Aphantasiacs who resonate with Lux’s point of view, like YouTuber Matthew Star. “I felt like I was missing out, like everyone else had this superpower of imagination that I couldn’t tap into. Researching it helped me to understand a lot of the reasons I think the way I do and explained how I have made workarounds in my everyday life,” he says.

But this point of view is just one part of the spectrum. “I do think it helps me to be more language-oriented,” says Julia Marsiglio, a 34-year-old, freelance writer from Montreal, Canada, “which is helpful to me as a writer. I think a lot in concepts and words. I think that typically when one type of sense is underdeveloped, another becomes more developed. I believe that my language centres in my brain are perhaps more developed because of my lack of mental visualisation.”

It is an age-old belief that creativity needs visualisation, but many Aphantasiac artists have proved it to be wrong time and again. “I am very creative,” Marsiglio tells Media India Group, “I am also very imaginative. Aphantasia simply means that I don’t visualise images in my mind, but that doesn’t mean I am not imaginative. In many ways I think it has made me more creative. It’s just that my innovation looks different.”

Imagination, another way

Lux explains that imagination is multi-faceted, “while visualisation can be a significant part of the creative process, it is only one aspect. For instance, if I said that I have a dragon that lives in my garage, that is using my imagination. You can visualise that, you can come up with the concept itself, and you can understand what the implications are and how that might play out. For me, I am great with the conceptual part, even if I cannot picture it in my mind. So, I am amused by thinking about a dragon in the garage, and I can think of different humorous scenarios that might arise from that, and I can work out stories from that idea. I can even have a concept of how that might work physically. I can’t picture it in my mind, but I have enough other tools in my imagination to work out the logistics well enough,” adds Lux.

Aphantasia like many other conditions has a spectrum. Any person can find themselves to be on a differing scale of visualisation. “Many people with Aphantasia can still have visual memory recall,” Swart tells Media India Group, “but many people with Aphantasia report less ‘rich’ dreams, memories, and imagined future scenarios.”

The belief is that most people with this condition were born with it but interestingly enough, some people have reported losing their ‘mind’s eyes’, due to Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, depression and anxiety.

In fact, Zeman’s first patient that came to him after losing his ability to visualise after going through a minor surgical procedure, led the neurologist to go deeper into the matter and eventually become the pioneer for his path breaking research into the matter.

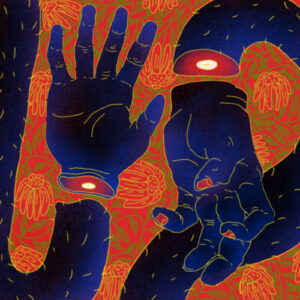

An illustration by Dan Lynh Pham

Many people might see it as a disadvantage but for many it is has worked as a blessing in disguise, “The pros to Aphantasia is that I feel as though I am a lot more in touch with my feelings and emotions because I don’t have a lot of distraction on my mind,” says Pham, “Not being able to daydream and visually explore ideas allows me more time for self-reflection and I think that makes me a lot more self-aware of myself and others around me.”

Star agrees with this sentiment. Traumatic memories can be very disturbing to people with visualisation but people with Aphantasia can stay in the moment, he says. “Traumatic imagery doesn’t bother me as I can’t recall it,” adds Star, “but it does have a lot of cons, I am currently in the process of discussing this and a potential ADHD diagnosis with my doctor and a psychiatrist, combined those two things basically leave me with a terrible memory. With no visual memory I can’t remember things like travelling or my family’s faces. I would definitely prefer to not have Aphantasia, but I don’t dwell on it day to day since I lived nearly 30 years without knowing I had it.”

Not just Visual

While Aphantasia, largely affects the mental visuals of patients, it should be pointed out that it does not exclusively impact the visualisation abilities. Dreams and music are very interesting topics to discuss in Aphantasia’s context. Dreams generally require a lot of visual imagery, while music requires recalling of the tunes, to lyrics.

For Marsiglio, dreaming is thorough and conceptual, just not visual, while on the other hand Pham claims to have extremely visual dreams, “I feel exceptionally present in my dreams, and they can feel very real. However, when I wake up, I can’t imagine what I experienced visually in the dream,” explains Pham.

Music, similar to dreams, lies on a pretty broad spectrum for Aphantasiacs. Pham says that she cannot recall lyrics, though she can recognise tunes, but can’t actually hum any of the songs. “Whenever I try to think about a song in my mind, I don’t necessarily hear the song in my head, but rather a version of me singing the song and humming a small portion of the song. I think this is why music has such an impact on me. My mind is really quiet, and all I hear is my own constant chatter, so music gives me a nice break from it,” Pham tells Media India Group.

On the contrary Lux claims to only hear words but has trouble recalling tunes. “The words and the melody come together and then I can sometimes recreate the notes afterwards, but most often not. I find it very difficult to recall tunes most of the time,” explained Lux.

For Marsiglio though, music has nothing to do with her condition, she informs that to her music is purely auditory, just with visual deficits. She can recall the tunes and words independently. Though she says that it’s a matter of where do you lie on the spectrum, “I am sure there are people who are much more adept at this and those who are less,” says Marsiglio.

Many people might think that this condition might have a negative impact on people’s lives but Aphantasiacs have again and again denied the claim, “I have lived like this my entire life,” says Lux, “and never considered it a disability or anything along those lines. In fact, I went 35 years without even knowing it was a thing. While I recognize some limitations that can arise from it, none of them have been debilitating or in any way problematic.”

Pham shares the same point of view. “I have never experienced life as a visual thinker, so I don’t feel as though I need to ‘fix’ or recover a mind’s eye. Growing up without the ability to visualize has led me to develop other ways of processing information and exploring ideas to compensate,” Pham tells Media India Group.