A chronicle of Pahari miniature paintings

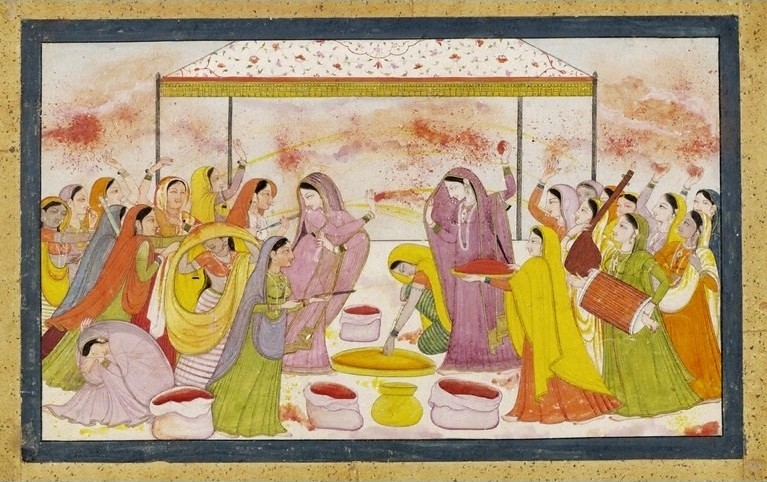

An impression of a Pahari miniature painting would ideally encompass a palm leaf drenched in colours, extracted purely from natural vegetation and minerals, with delicate complex detailing unified together in a creation depicting natural surroundings.

The Pahari miniature painting school flourished in the foothills of the Himalayas in northern states of Himachal Pradesh, Jammu & Kashmir and Uttarakhand from around the 16th century. The earliest surviving paintings from the school is the mid-16th century manuscript of the “Devi Mahatmya” illustrating early Rajput style of art, currently preserved in the Shimla museum. With patronage from the rulers of 30-odd Pahari kingdoms that existed in the region, the Pahari miniature school progressed and the art form reached its peak popularity between the 17th and 19th centuries.

Similar in style to the Rajasthani miniatures, a Pahari miniature painting usually begins with combining sheets of paper to achieve an appropriate thickness followed by an outlining, usually done with a dark colour and finally the colours are laid on. Unlike a modern-day artist’s brush, the painters of the epoch had to make their brushes from horse hair or feathers of local birds. Exquisitely so, the use of gold dust and river stone was made to brighten the painting and peculiarly so, a poison derived from the poisonous plants was also utilised to prevent the paintings from decaying.

With their own uniqueness, a variety of styles surfaced but the two major styles whose manifestation gained recognition are Basohli and Kullu style, and Guler and Kangra style. Basohli and Kullu style had its bold, intense tones blending the Hindu mythology with local folklores using the Mughal techniques. Under the patronage of Raja Kirpal Pal, the artist Devidasa painted the Rasamanjari text. In sharp contrast, the Guler and Kangra style of art focuses on cool and calm colours. The gradual decline of Basohli style gave rise to immense popularity to the Guler and Kangra style. This style of paintings mostly focused on landscapes adding elegant and graceful women in the foreground.

The Pahari artists not only attained fame but also received huge patronage from mostly the kings as they were called upon by many royal families to paint the Kings and their courts, fight scenes, armies on horses and elephants, shikar (hunting), love and other scenes. The great ruler of Kangra, Maharajah Sansar Chand (1765–1823 AD) is recognised as one of the biggest patrons of this form of art and is credited with making the Kangra school of art an eminent branch of Indian art of the period.

B N Goswamy, an art historian and critic made a revolutionary leap in the 1960s when he reconstructed the family lineage of Pandit Seu whose two sons Nainsukh and Manaku went on to become canonised figures in the field. Manaku, the elder son, borrowed his style directly from his father’s style of art while Nainsukh extensively learned Mughal techniques of art. A feudal lord of Jasrota, Raja Balwant Dev patronised Nain Sukh immensely. The artists went on to develop close connections with the king. The artistic legacy and ethos of the two brothers was continued by their sons around 1760.

A saying that “art is never finished, only abandoned” seems to take a literal turn in respect of the Pahari miniatures. It is common to discover old sketches, incomplete or unfinished paintings done by the previous generations of artists from this school. The end of feudal system and independence of India signalled the end of the golden era for the Pahari school as the sole patrons of this art form disappeared from the scene and with them, even the art form seems to have died out.

Vijay Sharma, a Padma Shri awardee painter from Chamba district and who has held several exhibitions in India and overseas, was recently quoted as saying that there was no government policy in place to preserve the Pahari style of paintings and that the very few teachers of Pahari paintings left were not in a position to pass on their legacy to the next generation due to lack of patronage from the government. The few families still engaged in practising the art have been reduced to making decorative panels for doors or windows and drawings.

Barely three centuries after its peak, the Pahari miniature school of painting faces an existential challenge and without immediate and significant government support or patronage by the new Maharajas of Indian business, this form could fade from the Indian canvas.