India’s Stance on Refugees

Biz@India

May 2018

India hosts the largest population of refugees in all of South Asia. At the end of 2016, there were 207,070 persons of concern in India, out of whom 197,851 were refugees and 9,219 were asylum seekers.

As per the Global Trends report on Forced Displacement in 2016, published by the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), by the end of 2016, 65.6 million individuals were forcibly displaced worldwide as a result of persecution, conflict, violence or human rights violations. In 2015 it was 65.3 million, with an increase of 300,000 people in the following year.

Even though the conflict in Syria has displaced around 12 million people creating the largest wave of refugees to hit Europe since World War II, India too has had to share the problems of a refugee crisis since the country’s independence in 1947. As of 2014, more than 200,000 refugees were living in India, according to UNHCR. India, in its 70 years as an independent nation-state, has seen its fair share of refugee problems, especially from its immediate neighbours. India hosts the largest population of refugees in all of South Asia. At the end of 2016, there were 207,070 persons of concern in India, out of whom 197,851 were refugees and 9,219 were asylum seekers, according to UNHCR.

Who is a Refugee?

A refugee is defined as “a person who owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it” – this definition is given by the Protocol relating to the status of refugees, a crucial treaty in international refugee law.

“India does not have any law on refugees but has been hosting refugees fleeing persecution in their homelands in search of safety and sanctuary since antiquity and hosts refugees as per its historical traditions of hospitality. India deals with different groups of refugees differently that deprives them equality before the law and equal protection of the law. India has been receiving refugees from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Congo, Eritrea, Iran, Iraq, Myanmar, Nepal, Nigeria, Pakistan, Rwanda, Somalia, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Syria, Tibet, etc. Therefore, India is home to diverse groups of refugees from all continents and regions of the world,” says Dr Nafees Ahmad who holds a doctorate (PhD) in International Refugee Law and Human Rights and is an assistant professor at the Faculty of Legal Studies – South Asian University, New Delhi.

India does not have any law on refugees but has been hosting refugees fleeing persecution in their homelands

Relevant Laws

The Government of India (GoI) presented the Citizenship (Amendment) Bill, 2016 in Lok Sabha (lower house of Parliament) on July 19, 2016. The Bill seeks to amend the Citizenship Act, 1955 where the acquisition and determination of Indian citizenship procedures have been enacted. The Bill aims to extend citizenship to an individual who belongs to minorities such as Buddhists, Christians, Hindus, Jains, Parsis and Sikhs hailing from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Pakistan who enter India without a valid visa or travel documents.

The entry of such persons in India shall not be treated as illegal. The refugees fleeing religious persecution from these countries see India as their natural home. Thus, the proposed amendment makes them eligible to apply for Indian citizenship by the process of naturalisation. The present citizenship law of 1955 treats such arrivals as illegal migrants. The Bill proposes to reduce the cumulative period of residential qualification from 11 years to six years for getting the Indian citizenship by naturalisation.

India hosts around 9,200 refugees from Afghanistan, out of which 8,500 are Hindus. There are also more than 400 Pakistani Hindu refugee settlements in Indian cities, mainly in the states of Gujarat and Rajasthan. Other refugee tribes like Buddhist Chakmas and Hindu Hajongs from Bangladesh have received refugee status in India. According to the 2011 census, 47,471 Chakmas live in the north-eastern state of Arunachal Pradesh alone.

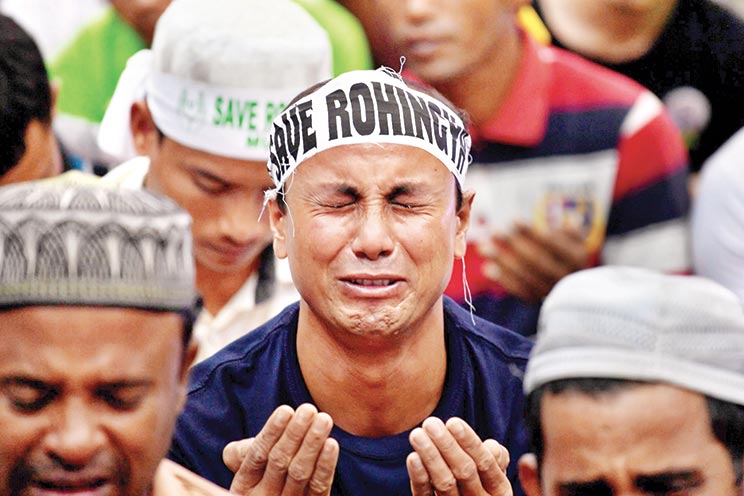

The most controversial refugee campaign happened last year when 40,000 Rohingya Muslims escaped Myanmar to take shelter in India. India has categorised the Rohingya as illegal immigrants and a security threat, siding with the Myanmar government. The Indian government has stated that the principle of non-refoulement, or of not forcing refugees to return to their country of origin, does not apply to India principally as it is not a signatory to the 1951 refugee convention. The office of the UNHCR has issued identity cards to about 16,500 Rohingyas in India, which it says helps “prevent harassment, arbitrary arrests, detention and deportation” of refugees. The UN described the Rohingya refugees as “the most persecuted refugee community” in the world that does not have the support of the global fraternity of nation-states.

The proposed bill does not apply to other refugees or migrants belonging to Muslim communities in India. “India’s stance on refugees is a cocktail of HARP (Hate Associated Religious Politics) that is being played to its crescendo. The GoI determines the status of refugees by ad hoc administrative decisions with a political tinge in the absence of any law. India copes with refugees and asylum seekers with the threefold strategy. Firstly, GoI grants full protection and assistance to refugees from Sri Lanka and Tibet. Secondly, refugees who get the asylum at the UNHCR level, and the “principle of non-refoulement” are applied for their protection, for example, Afghans, Burmese and Somalis, etc. Thirdly, refugees who are neither recognised by the GoI nor the UNHCR, but have arrived in India and got assimilated with the local populace, for example, Chinese refugees from Myanmar living in the state of Mizoram and West Bengal. Thus, the GoI deals with these refugees differentially as domestic political power permutations are central to their treatment. Mainly, Sri Lankan and Tibetan refugees got refugee identity documents, and they are provided a range of legal benefits. Tibetan refugees live in settlements and enjoy unbridled freedom whereas the Sri Lankan refugees are kept in camps under surveillance with restricted mobility. On the other hand, refugees from Myanmar, Palestine, and Somalia do not get any aid and assistance from the GoI, and they are discriminated and deprived of access to essential resources for human survival,” said Dr Ahmad.

But even though India doesn’t have strong laws to protect the refugees in the country it is doing far better than other developed countries. Today, 80 pc of the refugees are hosted by the Global South, and only nominal 0.02 pc refugees are hosted by the Global North despite the fact that the geopolitical and geo-strategic agenda of the Global North countries is responsible for the global refugee generation and migration.

The developed countries follow a policy of ‘Restrictionism’, particularly in the United States of America (US) under the Trump Administration that has undercut the US Refugee Resettlement Program, and many countries of Europe are tightening their immigration laws to deprive and deny entry to refugees and asylum seekers.

“India has always hosted refugees without any discrimination based on religion, race or region. The Supreme Court (SC) of India has done an exceptionally excellent service to the cause of refugee rights. In the absence of refugee law in India, SC has interpreted the word “person” in the Article 21 of the Constitution in an unprecedented judicial tradition. According to the judicial interpretation of the SC, the term “person” also includes non-citizens. Therefore, SC has addressed and appreciated the plight of refugees in many cases. Mainly, the cases of Khudiram Chakma v. State of Arunachal Pradesh and Ors, (1994 SC 615), and National Human Rights Commission v. State of Arunachal Pradesh, (AIR 1996 SC 1234) whereby the SC held that “all the refugees living in India have the right to life and the personal liberty” as enshrined in Article 21 of the Constitution of India. The ‘state is obligated to protect the life and freedom of each, be a citizen or otherwise, and it cannot permit individual or group of individuals to threaten the refugees, to leave’,” adds Dr Ahmad.

History of Refugees in India

Starting from the partition to the Rohingya crisis, the country has witnessed major refugee inflows.

1947: Massive population exchanges occurred between the two newly formed nations – India and Pakistan. Based on 1951 Census of displaced persons, 7.226 million Muslims went to Pakistan from India while 7.249 million Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims were forced to move to India from Pakistan, immediately after partition.

1959: The next major movement of refugees towards India happened when Dalai Lama, along with more than 100,000 followers, fled Tibet and came to India seeking political asylum.

1971: During the Bangladesh Liberation war, nearly 10 million refugees migrated from the country to India.

1983: During the Sri Lankan Civil war, more than 100,000 Sri Lankan Tamil refugees entered India and the number increased to 700,000 in the next 20 years.

1979-89: More than 60,000 Afghan refugees came to India in the years following the 1979 to 1989 SovietAfghan War.

2012: After the communal violence in the state of Rakhine in Myanmar in 2012, nearly 40,000 Rohingyas have their home in India now.