Budget 2020-21: A battle of unequals

Union finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman and a team of officials, shows the ‘bahi-khata’ containing the Union Budget 2020-21 documents at the Parliament in New Delhi on February 1

With consumption at a four-decade low and unemployment at a 45-year high, finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman missed the opportunity to use the budget to boost the economy and mitigate the problems of rural India.

The Indian budget for fiscal year 2021, starting in March, was presented a few days ago, amidst large-scale social and political unrest over the Citizenship Amendment Act. The budget was challenging for the government also due to the unprecedented economic situation as India’s growth rate had plunged to an 11-year low of below 5 pc in 2019-20, led by a slump in consumption and investment. Analysts had predicted that the government might take bold steps to power India back to faster growth but were left disappointed. The country’s benchmark stock index slid more than 2 pc even as Sitharaman was finishing the longest-ever budget speech, which she had to curtail abruptly after nearly 160 minutes.

As the economic distress has been growing in rural India and also amongst the urban poor, one of the biggest expectations from the budget was that the government would use the budget to propel consumption, mainly by putting more money in the pockets of the poor. Thus, an increase in social spending was almost uniformly expected, alongside continuation of reforms that could finally get the private sector investment restarted. The importance of boosting consumption through social spending had become starkly evident as even the bold move by the government to dramatically slash corporate tax rates has failed to lead to any investment, even six months later.

However, the government, struggling with sharply rising deficit, decided to curtail the allocations for the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Program (MGNREGA), one of the principal sources of income for rural Indians, especially farmers. Similarly, the spending on education, healthcare, nutrition and rural employment has been cut again, despite the fact that a number of economists have been repeatedly urging for measures to improve the incomes of the rural masses to boost the consumption demand. However, over the last six years, each year the allocations for rural schemes seem to be falling.

This year, the government has allocated INR 615 billion for MGNREGA scheme, a cut of over 13 pc vis-a-vis last year’s revised estimates of INR 710 billion. Similarly, other rural schemes such as PM Gram Sadak Yojana, PM Awas Yojana have not seen too much of an increase in allocation. “The budget does not have any vision or substantial new policy to address the problems of rural India,’’ Mahesh Vyas, managing director and CEO, Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) tells Media India Group. “The government needs to recognise these problems. The government seems to be in a denial of the problem of unemployment. Its lack of recognition of the problem is reflected in the cut in the MGNREGA funds,” adds Vyas.

The budget also lacks the vision to craft a policy and allocate suitable funds to address the myriad problems. Rural distress has risen to alarming levels with the decline in food crops, the devastation wrought by droughts and floods and the high proportion of uncultivated lands. As per the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) of 2017-18, rural unemployment has increased by 8 pc from 2011-12, and overall unemployment is the highest in the 45 years. At the same time, declining tax collections and sharply rising fiscal deficit mean that the government does not have the money to launch a credible rescue act to save the economy which grew at its slowest in almost a decade.

The agriculture sector, employing nearly two-thirds of India, grew at barely 2.5 pc during the first four years of the Modi government and the situation has not been very different since. When almost 70 pc of the population grows at 2.5 pc, it is bound to impact income and spending patterns. Even after the global humiliation of India scoring poorly on the Global Hunger Index, in the company of some of the poorest African nations, nutrition and hunger hardly find a mention in the budget speech this year.

An opportunity missed

Despite the deficit and falling tax revenues, the budget was the perfect opportunity for the government to set the economic story right, by focusing on the poorest sections of the society, which are incidentally also the biggest sections of the country’s population. It was also the opportunity for Prime Minister Narendra Modi to put into practice his oft-repeated slogan of ‘Sabka Saath, Sabka Vikas’ (With everyone’s support, development for all). This is crucial to address one of the biggest challenges that India faces today, and which will become even more severe in the future.

A report by British charity, Oxfam, released at the World Economic Forum’s 50th annual meeting last fortnight, highlighted the growing inequality in Asia’s third-largest economy, where the richest 1 pc of the population controls 42.5 pc of national wealth, while the poorest 50 pc have 2.8 pc. This means wealth of top nine billionaires is equivalent to the wealth of the bottom 50 pc of the population.

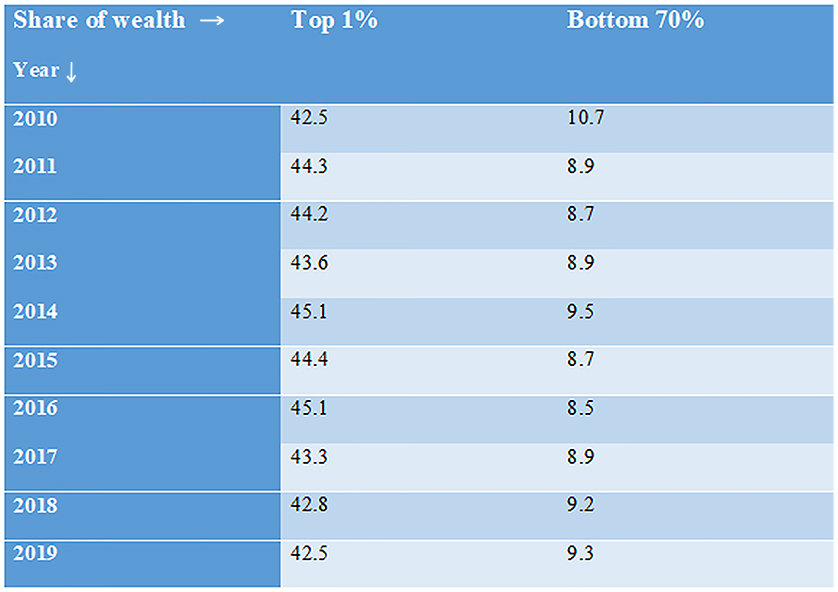

Oxfam India shared some data with Media India Group to show that inequality in India has widened over the past decade, with the pace of growth in inequality, accelerating over the past six years as the government continues to focus on big business, while leaving the hundreds of millions of poor fending for themselves. The challenge for the government is to create well-paying jobs and to look for more progressive taxation; incentivise loans and facilitate ease of doing business for small firms and startups. As suggested by Nobel laureate Abhijit Banerjee, the government ought to reintroduce wealth tax.

Data points from 2010 to 2020 after evaluating inequality

“The budget does not seem to recognise the problem of inequality in India. Inequality is not measured and so not recognised. Even measurement of poverty has stopped. The Modi government has made no efforts to measure poverty or inequality. It does not speak of these issues,” says CMIE’s Vyas.

Oxfam has argued for hiking corporation taxes as India slashed them recently. Oxfam International believes that if the richest 1 pc paid just 0.5 pc extra tax on their wealth, over 10 years this could finance creation of 117 million new jobs in childcare, education and health. “It appears to me that the government believes that there is some innate goodness and dynamism in India that is hidden under a layer of leftist interpretation of history and corruption by past governments. And, a new political order under a charismatic leadership should automatically peel away this layer of negativity. A great shining India should emerge once this layer is peeled away. Issues like poverty and inequality do not belong to the new narrative. They belong to an old narrative. The current government apparently does not subscribe to the views of yesterday that revolved around poverty and inequality. These beliefs aside, the budget does not allocate resources to reduce poverty or inequality in any way,” says Vyas.