Indian Economy in 2018

Biz@India

May 2018

As India enters the last year of the fiveyear term of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, the Indian economy stands at an extremely crucial crossroad. Domestic factors point to sustained growth, but global issues, notably the sharp and seemingly incessant rise in crude oil prices, could derail the economy and upset Modi’s economic reform agenda as he prepares for elections next year.

I n the beginning of 2018, predictions for the global economy were extremely positive, due to the recovery in Europe and the healthy growth in the United States of America (US), as well as recovery in Chinese growth and a better performance by other emerging economies. Expectations had jumped since November last year, following the announcement by the US President Donald Trump of a hefty tax cut for American companies that boosted not only their bottomlines by bringing in billions of dollars in additional profits but also led to a sharp rise in the stock markets.

In India, 2018 is being seen as an important year for economic recovery, mainly because the previous six quarters had seen two major shocks, given by the government of the day. First was banishing over 86 pc of the cash in circulation by replacing the 500-rupee note with a new one and banning the 1,000-rupee note. Demonetisation, as it is called, was extremely unsettling for a country where over 80 pc of the economy is informal and cash-driven and led to serious consequences for millions of small and medium enterprises all over India, as they struggled to pay wages and buy material.

The second shock, albeit in the form of a major reform, was the implementation of a uniform tax code, Goods and Services Tax (GST) that was meant to replace dozens of federal, state and municipal taxes with one tax. However, the scheme was badly designed and terribly implemented, leading to a total chaos in the economy. As a result, in July 2017, after GST was implemented, the economy suffered its second shock in barely nine months.

The two shocks led to the fall of economic growth from over 7 pc to around 5.5 pc and mounted pressure on the central bank to take steps to boost the Indian economy and bring it back to over 7 pc growth.

Hence, most analysts have been hoping for a return to strong growth in the fiscal that started on April 1, 2018. There are signs of some recovery in the economy, with key indicators such as manufacturing Purchasing Managers Index (PMI) that rose marginally from 51 to 51.6. The growth was largely on the back of consumption and intermediate goods, though, worryingly the investment goods continued to decline for yet another month.

The government itself has been optimistic about the outlook for the current fiscal year. According to the economic survey, an annual report on the state of the economy presented to the Parliament a day before the presentation of the annual budget, the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth in the year was expected to be between 7-7.5 pc, as against around 6.75 pc in the preceding year. It also admitted that while the industrial growth had slowed from 4.6 pc in 2016-17 to 3.2 pc in 2017-18, it expected a pick up in the rates in the current year, not only because of the domestic factors, but also due to the improvement in the global economy expected this year. The survey also said that in the medium term, the government would focus on areas like agriculture, job creation and education.

Eyes on Elections

By clearly indicating its focus on issues that matter the most to the common people – farming, jobs and education – the government has already let it be known that this year would not necessarily be remembered so much for pushing forward the ongoing economic reforms as for soft or outright populist policies that can help the ruling party garner votes, not just in the Parliamentary elections that are slated before next May, but also in the various states that will hold elections in the interim.

Hence, not much progress should be expected in the next batch of reforms that have been in the pipeline for a while, including most crucially, the labour reforms. India’s archaic labour rules have been one of the biggest pain points for most domestic and foreign investors as it has made firing workers a cumbersome, time consuming and expensive process, while the work inspectors continue to run havoc on employers through their corruption and misuse of discretionary powers, which are aplenty.

Also, to simplify the web of rules governing employers, the government has planned consolidation of 44 labour laws into four codes – industrial relations, wages, social security and occupational safety, and health and working conditions. Of these, the government has managed to introduce only the Wage Code Bill and that too in face of stringent opposition from all trade unions, including the union of the ruling party, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). The government did announce extension of fixed term contracts for all sectors, which itself is a significant change from the previous system. The fixed term contracts would help companies hire workers for seasonal activities.

Though the Wage Code Bill is expected to feature in discussions in the Parliament later this year, the government is unlikely to steamroll it, not only due to the unions’ opposition, but also to prevent the principal opposition parties from getting a handle on an extremely sensitive subject a few months from the elections. Thus, the labour reform could very well have to wait for a new government next year.

This principle could also apply to practically all the Free Trade Agreements (FTA) under discussion, including the European Union (EU)-India FTA and a post-Brexit United Kingdom (UK)-India FTA. The government has also not moved towards bringing some key elements such as petroleum products, real estate and alcohol under the aegis of GST, leaving a wide array of taxes in place on these goods. The government has also failed to revive private investment in the country, which has registered a paltry growth of 1.6 pc last year as against the GDP’s growth rate of 6.75 pc. As a ratio of GDP, the Gross Fixed Capital Formation has dropped from 34.31 pc in 2011-12 to 29.55 pc in 2017-18. This points to a severe risk as investment has to be led by private sector if the economy is supposed to be humming along smoothly. It also means that the Indian economic growth is hostage to the health of government finances and its ability to finance such growth through investment.

Caution: Sharp Dips Ahead

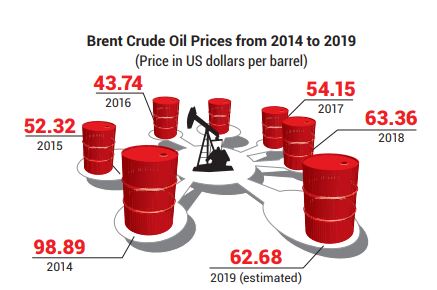

Consequently, it is this ability of the government to continuously finance the growth that will be severely tested this year. The government is already behind its target in reducing the fiscal deficit, which it had aimed to bring below 3 pc by now. Despite enjoying extremely favourable mix of domestic and international conditions, including notably very low prices of crude oil, which is the biggest bugbear of Indian central bankers as India imports nearly 80 pc of its consumption and when the prices fell from the peak of about USD 140 per barrel in early 2014 to the range of USD 40-50 USD a barrel, it stayed there for most of the period until early this year.

In a smart ruse, which explains the government’s capacity to invest, instead of passing on the benefit of low international prices to the consumers, the government has consistently raised taxes on crude oil, keeping the price at the petrol stations much higher than had been warranted by the low prices. These additional taxes allowed the federal government to raise additional revenues of about EUR 21 billion, that were used as the cushion for keeping the fiscal deficit in check and for investment in infrastructure development.

However, with crude prices now touching USD 80 a barrel, the price for Indian consumers is higher than even when the crude was at USD 140. This has put tremendous pressure on the government, which is unable to explain the record high prices at Indian petrol stations when the imported price is still about 45 pc lower than the price in 2014. Sooner than later, the government will be obliged to cut the taxes and see its deficit ballooning, accompanied by a corresponding rise in the inflation, which too had been benign since the beginning of the term of this government, on the back of low crude oil prices.

The situation has become even more challenging as rising crude oil prices and good growth in the US have strengthened the US dollar and the Indian rupee has slipped considerably, having lost close to 7 pc since the beginning of the year, reaching a record low in May and most analysts are predicting a further fall to about 70 rupees to the dollar, meaning a weakening by another 4 pc this year.

The country’s central bank, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), had estimated that an average price of USD 78 a barrel would shave off 10 basis points from its forecast of 7.4 pc in GDP growth this year. It also believes that this price could lead to 30 basis points in the inflation growth rate, hence forcing the bank to turn hawkish in its monetary policy. Analysts are already betting on the inflation rising from the current 4 pc to over 6.2 pc in the next quarter, meaning the RBI will be forced to raise rates faster than expected and to a higher level than had been predicted last year. A higher inflation will further sink the rupee, which is already the worst-performing major currency in Asia and next only to Brazilian real amongst the BRICS economies.

The weak rupee can also put India in a vicious cycle. Higher crude oil prices will drive inflation higher in India, which will make the rupee sink further making imports more expensive and further driving the inflation. This was the situation in late 2013 and early 2014 when inflation threatened to hit double digits and pushed economic growth off the track. Analysts believe that every USD 10 increase in crude prices adds to 0.4 pc in the current account deficit as a ratio of the GDP, putting India at a risk of seeing its current account deficit rise from about 1.5 pc to over 3.5 pc of the GDP in the next few months.

It is not just the current account deficit which is at risk – the government’s own fiscal discipline is seriously threatened by the present situation. With key elections in three states, all ruled by the BJP and at least two of them where the opposition, Congress party is expected to give a tough fight to the incumbent BJP governments, most analysts expect the government to cut the taxes on petrol by at least INR 5 a litre or about 20 pc of taxes levied currently. Some analysts predict that such a cut could widen the fiscal deficit by 25 basis points. Most analysts expect the government to miss its target of keeping the deficit at 3.2 pc of the GDP and instead end up at least with 3.5 pc.

The slippage will be punished by the rating agencies that even in the best of the times have kept India near the junk status. In late May, Fitch, a ratings company, affirmed India’s long-term foreign currency issuer default rating at ‘BBB-’ with a stable outlook, adding that the country’s weak public finances were a constraint on ratings. The yield on the 10-year sovereign note has already surged to 7.76 pc from 7.33 pc at the end of December.

Another headache for the government over the last year has been the significant rise in dud loans in the banking system, especially the public banks, which are believed to be sitting on bad debts exceeding USD 210 billion and over 60 pc of them are believed to be in about 20-odd public sector banks, while even the larger private sector players have been struggling.

Almost all public banks are being closely monitored by the RBI, which has banned a few of them from increasing their expenses or giving out fresh loans. The government is expected to inject a further EUR 6.2 billion in the banks this year, but this is hardly enough to restore the banks to a degree of health or even restore customers’ faith in the solvency of these banks.

A Tightrope Walk

With elections, state and parliamentary, now less than a year away, the Modi government will have to be especially careful about managing the economy. The government’s own economic survey highlighted that against the emerging macroeconomic concerns, policy vigilance will be necessary in the coming year, especially if high international oil prices persist or elevated stock prices correct sharply, provoking a sudden stall in capital flows.

The Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), which had been flooding in the country, has now hit a plateau, with many investors lured by rising dollar and the rise in US interest rates. Lower FDI could also balloon the current account deficit of the country.

Despite these conditions, the government’s agenda for the year is quite loaded. It needs to further stabilise the GST, privatise Air India and most importantly look out for the oil shock that may be around the corner and take steps to protect the economy from it to the extent possible.

Making its task tougher is the promised public healthcare for over 500 million people belonging to the economically weaker sections of the society and the promise to double the guaranteed price that the government pays to the farmers for their crops. The government has not yet disclosed how it plans to finance these schemes, which would cost tens of billions of euros each year. Yet, they are bound to drain the government’s already tight wallet.

How Modi manages to walk his talk would pretty much decide the winner in the state elections this year and the Parliamentary next year.