A low-key Lokpal remains a toothless anti–corruption watchdog

In 2011 Anna Hazare launched a campaign against corruption & launched a hunger strike at Jantar Mantar in New Delhi

Nearly seven years after the Lokayukta Act came into effect, the much-vaunted anti-corruption ombudsman has failed to make an impact, despite the establishment of Lokayukta in all the states, the state governments and politicians are deliberately weakening the institution by not providing adequate infrastructure, sufficient budget and workforce, says a report by Transparency International India, a global anti-corruption body.

In addition, many top political thinkers of the country openly opined that the quality of democracy and the ability to engage in democratic dissent has shrunk drastically, the report says. “Apart from that, many of the Lokayuktas lack prosecution powers or suo motu powers and many of the state-level acts have not yet been amended on the lines of the Lokpal and Lokayukta Act 2013. The independence and space for civil society are increasingly being contested,” says Transparency International India.

“It has been around 50 years since Maharashtra appointed Lokayukta in 1971; 10 year of the famous Anna movement and seven years of the Lokpal and Lokayuktas Act, 2013. But in actuality, there is little progress in the anti-corruption landscape of the country,” the body says in a statement.

The report goes on to say that many civil society organisations (CSOs) and activists who speak truth to power and shed light on the actions of politicians and public officials have found themselves targeted by government authorities by almost all parties ruling Union or States in recent time. “The government uses such tactics as restrictive legislation to deny CSOs their right to register, and in some cases suspends or withdraws CSO registration to operate. Resourcing of CSOs is also being targeted: some CSOs have been prevented from receiving funding from external sources, and some have had their bank accounts suspended, stopping them from accessing funds to carry out their activities,” it says.

The contrast between the current situation and the one that prevailed about nine years ago could not have been starker. On April 5, 2011, social activist Anna Hazare launched a campaign against corruption and launched a hunger strike at the Jantar Mantar in New Delhi. His key demand was that the Indian government pass the long-pending strong Jan Lokpal bill which had been hanging fire for decades as no political party had showed any desire to install an ombudsman to oversee the government’s functioning. A Lokpal bill had been introduced by various parties on nine occasions between 1971 and 2008, but the bill never made it past the Parliament.

But Anna Hazare’s hunger strike in 2011 gave birth to India Against Corruption movement, one of the biggest civic movements of independent India, perhaps with the sole exception of the movement against emergency. It was also featured by the TIME magazine as one of the biggest news stories in the world that year. Four days into the fast, the government set up a committee with equal representation from the civic society to draft the bill.

Hazare was unhappy with the draft bill presented to him and he threatened another hunger strike in August, but he was arrested before that. After several smaller intermittent protests, Hazare launched yet another hunger strike in December 2013. The nine-day fast ended when the bill had finally been passed by the Parliament.

Haphazard implementation

Besides the passage of the bill, the only concrete outcome of the movement, in the past seven years, has been to send the Congress party to the political wilderness and the emergence of a strong Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) led by Narendra Modi. The current government that came to power on the slogan of “Zero-Tolerance” against corruption, blindly ignored the main goal of India Against Corruption movement. It wasn’t a big surprise as Narendra Modi himself had fought against the appointment of a Lokayukta during his reign as Gujarat chief minister.

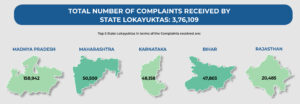

The implementation of the Act has been carried out in a half-hearted manner by governments – both central and states. Out of the 28 states and 3 union territories, the post of Lokayukta is vacant in 8. Moreover, only four states – Bihar, Manipur, Odisha and Tamil Nadu – have appointed judicial and non-judicial members of Lokayukta. Some states have put a fee that effectively can be a barrier for most to approach the Lokayukta. The fee ranges from INR 3 in Himachal Pradesh to INR 2000 in Gujarat and Uttar Pradesh.

Another reason behind the limited efficiency of the institution has been a weak law that does not grant them adequate powers and effective autonomy. Transparency International says that other states could adopt the Karnataka and Kerala Lokayukta Acts which could be considered model state level laws.

Another challenge for Lokayuktas’ effectiveness is the lack of digitalisation of the office. At a time of rapid adoption of digital services across the country and the globe, most Lokayukta offices are handicapped, with as many as 10 states that do not even have an official website or websites that can be accessed by the common people, the report said. “Lokpal (Email mode) and three states namely Odisha, Maharashtra and Mizoram have online complaint facility,” it says.

Reinforcing Lokayukta key

Transparency International says that to make the Lokayuktas efficient and be able to fulfil the responsibilities as per the law, several measures need to be taken.

It has called for strengthening of and giving a free hand to anti-corruption agencies, notably the Lokayuktas (Union & States), vigilance, Central Bureau of Investigation, and making them more independent and autonomous. Transparency International recommends imposing criminal culpability for government interference in their functioning.

To make them truly autonomous and free of government, Transparency says that these agencies need to develop their own dedicated cadre of officers who are not bothered about deputation and abrupt transfers as well as bold head of institutions. “It is also possible to consider granting these anti-corruption agencies and other federal investigation agencies the kind of autonomy that the Election Commissioner of India enjoys— only accountable to Parliament,” the report says.

One way out is a more efficient parliamentary oversight over these agencies, in order to ensure better accountability, despite concerns regarding political misuse of the oversight. The report also says that various courts including the Supreme Court and many High Courts while dealing with the issue of appointment of Lokayuktas failed to achieve any success.