French journalists on streets against Macron’s law

Human rights and freedom advocates as well as the entire media fraternity of France call the law a draconian attack on freedom of expression

Amidst heated debates, the French Parliament passed a new law last Friday banning publication of photographs of police personnel on duty. Proposing the law, French interior minister Gerald Darmanin said it was meant to protect the French policemen from harassment or attacks on social media and cited the numerous incidents of clashes between protestors and police in France.

The law has been staunchly opposed by French media, cutting across ideologies or size of the media and thousands of journalists have been hitting the streets in protest against the law that dramatically reduces press freedom in the country.

The damage that the law could cause to the press freedom had already become clear days before the law was passed by the Assemblé Nationale. On Tuesday, a journalist working with the state-owned France 3 television channel was detained while he was filming a protest against the law in front of the Assemblé Nationale building. The protest had led to a violent clash between the demonstrators and the police and when the police were arresting, the journalist was also picked up even though he showed the press card to the police officials on duty. He was detained through the night and released without charges the following day.

The detention caused a furore in the country with most human rights and freedom advocates as well as the entire media fraternity of France calling the move a draconian attack on the freedom of expression. French interior minister Darmanin added fuel to the fire by saying that neither the journalist nor France 3 had informed the Prefecture de police (regional police headquarters) that their journalist would be covering the demonstration. This enraged the entire media community in France which categorically said that they would not be accrediting their journalists for covering protests, but they would continue to exercise their freedom and right to cover and report on any event across the country.

Caught off guard by the strong backlash that the law, called Article 24 of Securité Globale, the French government proposed a change saying that would keep the law intact while exempting registered media

Caught off guard by the strong backlash that the law, called Article 24 of Securité Globale (Comprehensive Security law), the French government proposed a change saying that would keep the law intact while exempting registered media. This amendment was also met with a voluble opposition from the press and human rights and freedom advocacy organisations across Europe saying that keeping an eye on the behaviour of police or military personnel on duty was the right and responsibility of all the citizens and not just the card holding journalists.

Reinforcing police state image

The new law does no favour to the French image of being a police state, both at home and abroad. Of the 28 members of the European Union, France enjoys the dubious distinction of being the one most cited by the European Court of Human Rights for violations of basic human rights, mainly by the police and security personnel. In 2019, the court delivered 19 rulings on France, of which 13 had found at least one violation of basic human rights.

According to Human Rights Watch, the police in France have been unabashed about their ways and methods and violation of basic human rights and discrimination are part of life for many, especially the minorities in the country. It says that abusive and discriminatory identity checks are a longstanding problem in France. As early as 2005, pent-up anger over police abuses, including heavy-handed identity checks, played a role in riots in 2005 in cities across France and appears to underlie countless lower-intensity conflicts between police and young people in urban areas and the poor suburbs.

“Statistical evidence gathered by social scientists and nongovernmental organisations indicates that Black and Arab men and boys, or people perceived as such, living in economically disadvantaged areas are particularly frequent targets for such stops, suggesting that police engage in ethnic profiling (that is, making assumptions about who is more likely to be a delinquent based on appearance, including race and ethnicity, rather than behaviour) to determine whom to stop,” says a report by HRW.

In 2014, the Defender of Rights, France’s independent human rights institution, issued reports in 2014 and 2017, criticising abusive practices and calling for reform. In 2016, the country’s highest court, the Court of Cassation, found that three young men had experienced identity checks based on profiling without any objective justification, constituting “gross misconduct that engages the responsibility of the state.

The police came under severe criticism for excessive use of force against participants in ‘yellow vest’ protests, including by Human Rights Watch, in 2018. The 2019-2020 protests over pension reforms have pitted citizens against police. High-profile deaths in police custody have focused the nation’s attention on police tactics like the “prone restraint,” or forcing a person to lie on their stomach while applying pressure to their torso. Police unions complain of unrelenting pressure, insufficient resources, and unfair criticism. In 2018-2019, a reported 94 police officers committed suicide.

At an anti-pension reform in the eastern city of Lyon earlier this year, a police officer fired a teargas grenade at students filming the crowd from the balcony of their apartment. Another one fired a flash ball at a demonstrator at point-blank range. At a gathering in the centre of Paris, police appeared to throttle Cédric Chouviat, a 42-year-old motorcycle courier, who later died with a broken larynx. These images forced the authorities to admit that police violence actually exists.

“We denounce a law that threatens freedom of expression, the right to protest and the right to privacy. This law proposes to treat the entire French society under the lens of the terror threat. This would have dangerous consequences for individual freedom,” warned Anne Sophie Simpere of Amnesty International France in an interview to a French media. The autonomous Defender of Human Rights Claire Hedon has also criticised the law and said the law could threaten personal liberties and fundamental rights. She also called for a withdrawal of Article 24 calling it useless and a potential nuisance in the hands of police.

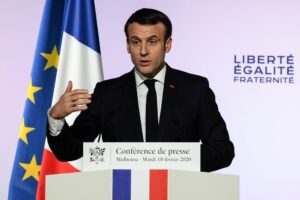

Macron’s rightward march

Despite the opposition, the law has been passed and so far there is no sign that the French government plans to withdraw it or modify it to address the issues and concerns raised by the press and human rights organisations. The law marks yet another shift by President Emmanuel Macron towards the right of the political spectrum.

For the past several months, Macron, facing heat from Marine Le Pen, leader of the extreme rightwing Rally Nationale, previously called Front Nationale. Le Pen has been leading Macron in opinion polls for the presidential elections slated for April 2022. With the political centre and mainstream left in France still in a disarray, Le Pen has emerged as the strongest rival to Macron and the economic distress that has accompanied the coronavirus pandemic has only strengthened her hand.

Le Pen has for long criticised successive French Presidents for their failure to beef up the police and security forces and actually cutting the budget allocated to security. These attacks are reinforced after each terror attack or violent incident targeting the police and security forces.

The Comprehensive Security law as well as declarations of a sustained state of emergency in the country, first in response to the frequent terror attacks and then in the aftermath of the coronavirus pandemic, are being projected by Macron’s party as a sign of a strong-willed President who is not afraid to take bold measures to strengthen the French State and its instruments.

But in trying to outdo Le Pen and project himself as a defender of the police and security forces, Macron may have overreached himself and the strong backlash by the media as well as civil society organisations is almost certain to backfire. It will also open Macron and France to charges of running a dictatorial regime and put him in the same league as some other European Union leaders like Viktor Orban of Hungary or Jaroslaw Kaczynski of Poland.

For a country that has liberty, equality and fraternity as its motto and which was the home to the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights, that is a big step backwards.