Nutrition malware hits women & children in India: NFHS5

Percentage of anaemic children aged between six and 59 months increased from 54.2 in NFHS-4 to 69 in NFHS-5 (MIG photos/Aman Kanojiya)

Data from the first phase of the National Family Health Survey (NFHS) (2019-2020) says that the proportion of stunted children has risen in several of the 17 states and five Union territories surveyed, putting India at risk of reversing precious gains in child nutrition made over previous decades. Worryingly, that includes richer states like Kerala, Gujarat, Maharashtra, Goa and Himachal Pradesh. The share of underweight and wasted children has also gone up in the majority of the states. Between 2005-6 (NFHS-3) and 2015-16 (NFHS-4), India had remarkable success in reducing stunting from 48 pc to 38.4 pc.

However, over the last five years, a lot of these gains have been lost, at least in a number of states, especially the economically better off states like Maharashtra and Gujarat as well as high literacy state like Kerala. The reversals in survey occurred despite a relatively healthy economic growth, better sanitation & access to cooking fuel.

Prachi Pandit, co-founder and director of Arbuza Regenerate, a company focused on addressing issues in population health, feels that the economic growth has very less to do with the malnutrition problem in India. “The economic growth has very little to do with reducing malnutrition in India as in this country malnutrition is likely to depend on direct investments in health and health-related programmes. To begin with economic growth would work to eradicate malnutrition only when the access to money is equal amongst all genders. We know that malnutrition is cyclic; an underfed mother delivers a malnourished child which becomes a malnourished parent later, it starts when the pregnant mother is eating low in terms of quality and quantity and this is mainly due to problem in all or one area; accessibility, affordability, awareness and aspiration. Unless you provide direct means to this mother it is unlikely that she will take care of her diet as food is her last priority,” Pandit tells Media India Group.

“Also the window of opportunity to improve malnutrition would ideally begin way before, when the targeted beneficiary is adolescent, and she is empowered and made aware. Now this would require means, funds but also right people on the field and targetted programmes which are region specific and last but not the least, malnutrition is not just a problem of information or economic growth of the country, it is a problem of implementation and well-designed programmes. It is also possible that economic growth over many years might not be sufficient to overcome the impact of intergenerational factors, such as the long-term and short-term nutritional status of mothers,” Pandit adds.

Misdirected government spending

Earlier this year, in February, to improve the health and nutrition profile of children and adults in India, finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman allocated INR 356 billion for nutrition-related programmes for the fiscal year 2020-21. It was 25 pc more than the INR 292 billion that had been allocated the previous year. However, several NGOs say that it is not just a question of allocating adequate budget. The impact mainly depends on the way and to the extent the budget is used, say the experts.

“It is actually worse, it reflects that government seems to be spending for wrong things or programmes. Most of these interventions are not well thought about keeping in mind the beneficiary, and how Indians are different in behaviour and biochemistry. It’s like shooting any bullets and hoping that it will hit the target and that does not work,” says Pandit.

“If you look at the budget, there are two big problems. One is that the budget is allocated, but a large chunk of it is not spent on the programmes. Instead, whatever spending happens, it is for the administrative purposes and thus budgeting has limited role to play in addressing malnutrition unless it is spent wisely and by the people who know how to maximise the impact of the spending,” says Girish Kulkarni, founder of Snehalaya, a leading NGO in Maharashtra that works with sex workers and children and runs large centres to take care of HIV+, disabled children as well as orphans and children of vulnerable families.

Unsurprisingly, the budgetary support does not seem to have made any significant difference. According to the rankings by Global Hunger Index 2020, which measures levels of undernourishment, stunting, wasting, and mortality rates among our children, India ranks 94th in 107 countries.

Snehalaya’s Kulkarni says that instead of involving domain experts from various NGOs who know the field and would make the programmes more efficient and impactful, the government has been pushing NGOs out of this activity. “The government is rolling back various programmes run by NGOs. These things have come to light recently. There have been so many rules created that it’s difficult to run an NGO in India today. The budgets and spending by a number of NGOs have also seen a cutback as a result of this. So there is budget but it’s not been spent properly and that is why these kind of malnutrition of figures can be seen. Money for beneficiaries never really reaches them. Earlier the kids used to get milk in Maharashtra, that has also stopped. Also the rations that were given in schools, there is no evaluation on whether the rations were made available to the kids or was it sold,” says Kulkarni.

As a result of misdirected government policies and priorities, the findings of the NFHS5 are a dramatic setback as far as nutrition is concerned. Pandit says the setback is huge. “The malnutrition indicators as have worsened, anaemia among children and women remains a matter of concern. The percentage of anaemic children aged between six and 59 months increased from 54.2 in NFHS-4 to 69 in NFHS-5. The percentage of pregnant women with anaemia increased from 53.6 in NFHS-4 to 62.3 in NFHS-5. Women aged between 15 and 49 with anaemia increased from 62.5 in NFHS-4 to 71.4 in NFHS-5,” she says.

Post-pandemic picture far from pretty

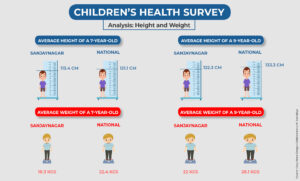

Most experts believe that as the survey was conducted before the Covid-19 pandemic had hit India, the situation on the ground now may be much worse than what has been reported in NHS5. “Our situation is at least twice as bad now as it would be in the survey which was conducted at a time when the government was saying that our GDP has risen sharply. However, during the lockdown, the economy crashed and GDP has crashed and I am certain that on all parametres, the situation is far worse now than during the NFHS. We have also done a similar survey in slums of Ahmednagar of children between 6-12 years of age and the findings show that the height and weight of slum children is much lesser than the average. As this was done during the lockdown, it is much more relevant than the NFHS5,” says Girish Kulkarni.

This was despite the fact that a large number of children had access to clean drinking water, regular meals, access to medical facilities as well as proper sanitation. The survey was designed and conducted by Curry Stone Design Collaborative, a Mumbai-based consultancy.

The survey in Ahmednagar showed a strong disconnect between malnutrition and access to civic facilities

Another factor that may have worsened the situation of malnutrition during the pandemic and the lockdown as the vulnerable families were only provided foodgrains, with key nutritional elements like vegetables and fruits missing. “At that time, the prices of these commodities rose dramatically and pushed them out of reach of most people, let alone the vulnerable families. Thus it is certain that the condition must have deteriorated sharply,” says Kulkarni.

What needs to be done?

NGOs and nutrition experts feel that the government should focus on empowering the beneficiaries and the NGOs first who are closely associated with these programmes.

“This is truly a big setback and time to reflect, on programmes, implementation and policies. We are talking about these problems forever and a day. It is high time to critically look at the not-so-obvious and obvious reasons for high prevalence of malnutrition in the country.

We need a multi-pronged approach, it is time when we move out of our silos and experts from agriculture, nutrition, public health biologist, and economist, community leaders, join hands instead of pointing fingers, it is the time to come together to make a difference, we need views and opinions and participation from all sectors. We need programmes around food quality; variety and diversity, we need better agriculture practices, we need better PDS, better economic strategies to involve and help empower the beneficiaries, we need better and deeper view from science and impactful programme design from Public Health experts and we need community to be involved at all these levels,” says Pandit.

Kulkarni says that one of the first things for the government to do now would be to conduct a large, in-depth survey to determine the exact extent of the impact of the pandemic on nutrition and that instead of taking only a few thousand families, it is better to broaden the survey by involving qualified NGOs and using digital technology in conducting the survey to determine the true picture and then get down to addressing it.