World Day Against Child Labour: Pandemic paralyses battle to end child labour

Thirteen-year-old Muskaan is a very shy and soft-spoken girl. So soft-spoken that one would be tempted incessantly to ask her to repeat herself. But Muskaan, who lives with her parents and 5 other siblings in a slum near Malviya Nagar in New Delhi, is emphatic that children should not be forced to work.

‘‘I used to feel like just leaving everything and running away. I used to do household chores as well like cleaning the house, washing utensils, cooking food. I used to sleep at 2 am after washing all the utensils. I had to go to work, who would have earned to run our house. I don’t like to work, people should not force kids to work, it does not feel good to work,’’ Muskaan tells Media India Group.

Living in the same slum, with her parents and 4 other siblings, Jyoti, 14, is more forthcoming and blunt about her dislike for being forced to work at a time when she ought to be studying. ‘‘Why is there this lockdown? I don’t like it at all as I can’t even go outside. I want to go to school. This is what I want. I don’t want to do this work. I wish that I get my life back as I want to live the way I used to live before,’’ she says.

They may be two adolescent girls, but Jyoti and Muskaan are strong evidence of the way the Covid-19 pandemic and devastated economy has forced children out of school and placed them at work, in order to help their families eke out a living amidst an unprecedented economic crisis, or rather meltdown, that India has been witnessing for well over a year.

Children pay price for pandemic

Jyoti and Muskaan also bear evidence to a report released by the International Labour Organisation and the UNICEF a couple of days ago that at least 9 million more children were forced to work again last year, making it the first global rise in several years. The pandemic has been nothing short of a catastrophe for the global battle against child labour. With almost all countries experiencing worst economic performances in over half a century and GDP falling anywhere between 5-12 pc across the world, the children seem to be paying a disproportionate price of the pandemic.

The children have had to deal with over a year of school closures and online classes have been disastrous in most families in most of the developing countries since many families and most children lack access to internet or a device for them to study online. With schools closed and family income under severe distress, due to job losses that reached several hundred million last year, there has been a sharp rise in number of children in employment again.

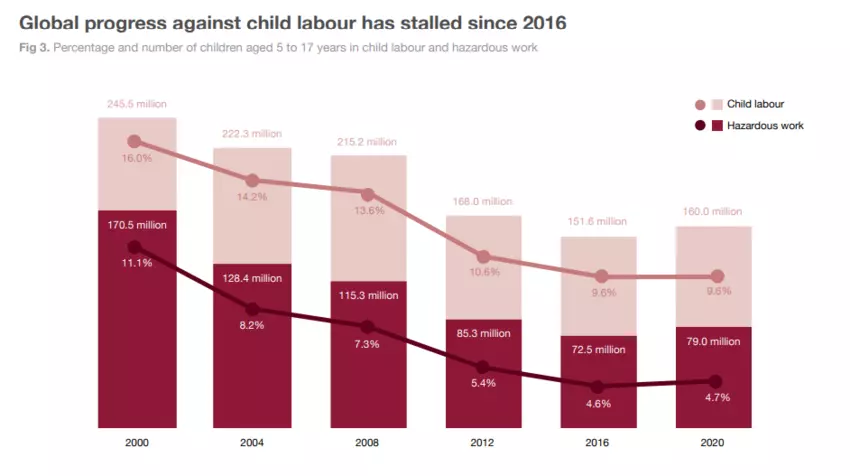

The UN bodies go on to say that the cases could rise five times as much should the economic situation worsen further than at the time of the survey. They project the number to go higher by as many as 46 million more children to 206 million by end of 2022, annulling the gains made by several decades of work by governments and civil society organisations across the world which had brought the number down from 245 million in 2000 to 152 million in 2016.

A report released by ILO & UNICEF says that at least 9 million more children were forced to work again last year (MIG photos/Aman Kanojiya)

Catastrophic as it looks, that estimate may also turn out to be very conservative when the dust settles on the pandemic. Many countries in the developing world, from South East Asia right through to Latin America have been struggling with the second wave of the pandemic that has proven to be much more severe and deadly than even the first one last year. It is too early for data to emerge from the worst-hit countries and those where data collection is delayed due to the pandemic and/or conflicts.

The report goes on to express special concern that unlike in the past when most children at work were rather older, the pandemic has seen a significant rise in the number of children aged 5 to 11 years in child labour, who now account for just over half of the total global figure. Also, the number of children aged 5 to 17 years in hazardous work has risen to 79 million.

India likely amongst worst hit

India, traditionally one of the worst offenders in child labour cases, had made tremendous progress in eliminating the malaise over the past two decade. The UNICEF-ILO report acknowledges the achievements made by India and all other countries in battling child labour since the turn of the millennium. From 2000 to 2016, the number of children in work had fallen dramatically by over 94 million.

This achievement had come on the back of sustained and healthy rates of economic growth and relative political stability in these two regions, as both economic progress and political stability are key conditions for ending child labour.

The only problem area remained in Africa where in the absence of either, child labour flourished, including the most inhumane form – use of thousands of children as soldiers in the dozens of ongoing chronic conflicts in the continent.

According to the International Labour Organisation, in 2016, there remained about 152 million children still in work globally and as many as 73 million of them performing hazardous work that placed their health, safety or moral development at risk. Africa was in the worst place where 20 pc of children were still involved in child labour.

According to ILO, in 2016, there remained about 152 million children still in work globally (MIG photos/Aman Kanojiya)

However, several Indian NGOs say that the pandemic has already led to a huge rise in number of children at work, primarily to support family incomes that have dwindled due to job losses or lockdowns. ‘‘The situation is going to worsen due to the pandemic. During the lockdown since everything was closed, that is why children were not used as labour in big numbers. However, since education of these kids has come to a halt and the situation is so pathetic as many families have lost their breadwinners or at least the breadwinner is out of job. So, children from these families will have to work. They will not be able to continue with their education. And they will have to work. The situation is the same in rural areas as well as urban areas,’’ warns Girish Kulkani, founder of Snehalaya, an NGO in Ahmednagar in Maharashtra that has been working on underprivileged and handicapped children as well as HIV-infected commercial sex workers and their children.

“You need not wait till post pandemic to see the rise. Right now, we are facing this kind of cases. Parents are not there for their children. Also, if a parent comes to you, you may not be willing to give any help, but if a child comes to you and begs for food or asks for work, you will definitely do that. So, it is easier and hence many children have started working in place of their parents. They are working as domestic helps. The first thing we need to do is provide them one square meal,” says Rani Patel is founder of Aarohan, an NGO based in New Delhi, that has been working with underprivileged children.

Long working hours

Children complain that now they end up working over 12 hours every day as they have to do household chores at their homes in addition to what they have to do at their workplace.

‘‘I used to leave for work at 9 am and come back at noon. After returning I used to cook food for home and hence, I could not do my online classes during that time. I came to Aarohan as we got food here. Then I rested for some time in the afternoon and went to work again in the evening and when I came back, I had to cook at home again,’’ says Muskaan, who had to do domestic chores at two households to earn some money. ‘‘I got INR 1500 at each place and during the lockdown, the employers gave us some extra money. Even though it was very tiring, but I had to go and work as my mother had to go to the village. If I didn’t go and work who would have taken care of expenses of the house?’’ asks Muskaan.

Jyoti’s story is absolutely the same. She says that after the lockdown was announced, her father lost her job and hence she was obliged to work. ‘‘I don’t like to go to work but I am helpless. I usually do not go out anywhere and stay at home. Right now my mother has gone to the village and that is why I have to work, both at my place and outside as well. I don’t have any money, even my sister and father are jobless that is why I have to go work. I wake up at 7am every day and do all household chores, after that I leave for work around 9:30 am and return at 12pm. After returning home I have to all household chores and take care of my younger brother as well. He stays alone at home, sometimes he helps, and sometimes he does not. I have to work the entire day. After doing all household chores I take a bath and leave for work again at evening to wash utensils in different houses,’’ recounts Jyoti.

Muskaan is very worried about the long-term effect that her long working hours may have on her health. ‘‘Some people say that children who work long hours, their height does not increase. Is this true?’’ she asks innocently, though hitting the nail on the head as nearly 2 in 5 Indian children suffer from stunted growth, but which is more a result of malnourishment than hard work.

Pandemic puts paid to UNSDG goals

Muskaan’s innocent query points to a challenge that experts at ILO, UNICEF and governments around the world have begun pondering over in the aftermath of the pandemic.

In September 2015, world leaders met in New York under the aegis of the United Nations and set up United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, identifying 17 broad and common objectives for the humankind to achieve by the year 2030, calling them Sustainable Development Goals (UNSDG). One of the key targets was elimination of child labour in all forms by 2025.

UNICEF-ILO say the number of children at work may rise by up to 46 million by the end of next year globally (weforum)

Months later, in 2016, it had looked like a pretty much achievable target especially in view of significant progress made since the turn of the century in reduction of child labour in Asia and Latin America, two of the three biggest areas where this problem had been rampant.

But barely two years of the pandemic has reversed most of the gains made over two decades. UNICEF-ILO say the number of children at work may rise by up to 46 million by the end of next year globally. This prediction applies to India more than any other nation as gross mismanagement by the political leadership of both the economy and the battle against Covid-19 has seen the country reel under unprecedented crisis for over 18 months now, there are reports of several hundreds of thousands of children having been forced back in work, reversing the impressive gains made by the country from 2000-16 period. Experts rule out India meeting the target of elimination of child labour in four years. ‘‘My biggest concern is that there are parents who are leaving their children behind and they are going back to their villages. The children are back to begging and other criminal activities. What we have noticed is that the other kind of social evil has generated out of this. If you ask me about the UNSDG goals or to eliminate child labour by 2025, in India at least it seems impossible. Because the economic situation is worsening every single day, even now,’’ predicts Rani Patel of Aarohan.

‘‘The situation in India is really bad. It was said in 2010 that Maharashtra will become free of child labour. And Maharashtra is one of the most progressive states in the country. Accordingly, all departments like labour department and child welfare department were given targets to put in place facilities like shelters for children and were told to take strict action against those establishments that employed children. Now the situation even in Maharashtra has worsened. If you ask me about this target of 2025, I think the situation will deteriorate even further because of pandemic,’’ adds Snehalaya’s Kulkarni.

Despite bringing the number of children at work down from about 14 million in 1990 to about 9.3 million in 2018, India still was a large source of this malaise at a global level. It would take a brave soul to guess how much higher two years of unprecedented economic shocks have taken this tally.