Modi visit to Paris fails to address bilateral trade, achilles heel of a blossoming partnership

Indo-French trade has stagnated at USD 13 billion despite close ties and frequent purchases of high-tech items

At the first look, the Indo-French relationship looks to be in the pinkest of health, with little need for anything to change as cooperation is flourishing in almost every sector of the economy and every aspect of social or people-to-people contact.

The year 2023 marks 25 years since the Indo-French strategic partnership began in 1998 and it has certainly stood the tests of time, as was intended by President Jacques Chirac and Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee, who in January 1998, in a world of change and uncertainty, elevated the Franco-Indian relationship to the rank of strategic partnership, the first such partnership for India.

As noted by Macron and Modi in their meeting in Paris, the bilateral political and diplomatic commitments are among the strongest and most reliable. The defence and security partnership covers everything from the seabed to space. As co-founders of the International Solar Alliance, the two countries are also on the same page in some areas of climate change and sustainable development, though there are stark differences that act as a global divide between the rich and the developing world. The ties also seem to be blossoming in areas of education, science and technology, and culture.

As is the norm on such occasions, a number of deals and MoUs were signed during Modi’s visit. On defence, though the final communique does not mention it, India has already let it be known that it has opted for 26 Rafale Marine fighter jets for its indigenous aircraft carrier INS Vikrant and three more Scorpene submarines to be manufactured by Mazagaon Dock Shipbuilders Limited in Mumbai.

In space, the two sides have agreed on launch of a joint earth observation satellite, Trishna, the first phase of the maritime surveillance constellation in the Indian Ocean and the protection of Franco-Indian satellites in orbit against the risk of collision. In nuclear energy, the two sides have also decided to cooperate on low- and medium-power modular reactors.

The two sides also agreed to boost the number of Indian students studying in France, while the French agreed to fund up to EUR 100 million for the second phase of India’s flagship programme on sustainable cities, in partnership with the European Union and KFW of Germany. Other funding agreements include USD 30 million in financing from Proparco for the South Asia Growth Fund (SAGF III) which will invest in companies promoting energy efficiency, clean energy and the optimisation of natural resources in the region as well as another USD 20 million financing from Proparco with Satya Microcapital for access to microfinance in India for the benefit of women in rural areas.

The sole agreement involving two private companies was the announcement of a partnership between McPhy and L&T on the manufacture of electrolysers in India. The fact that of the 20-odd agreements and MoUs, on such a high-profile occasion, only one featured private firm from both the countries indicates the degree of challenges that await development of bilateral business relationship between India and France.

Trade remains weak link

Despite enjoying such close relations, the Indo-French business and commercial relations have failed to grow. In 2021, the total value of bilateral trade between India and France was barely USD 13 billion, having taken 11 long years to rise from USD 9 billion in 2010. This makes France one of the smallest trading partners of India in Europe and one of the slowest in terms of growth, despite frequent purchases of aircraft, submarines, missiles, satellites and other high technology items by India from France.

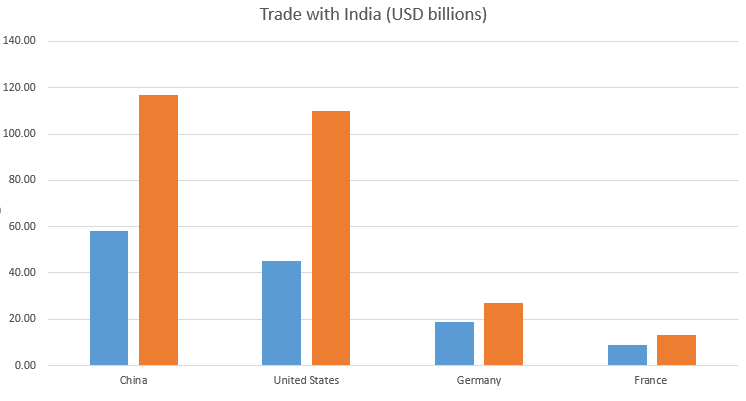

In comparison, almost all major countries have seen skyrocketing increase in their trade with India. Despite the political tensions and border conflicts between India and China, the Indo-Chinese bilateral trade has risen from USD 58 billion in 2010 to USD 117 billion in 2021, making China the largest trading partner of India.

Similarly, the United States has seen its trade with India balloon from USD 45 billion in 2010 to USD 110 billion in 2021. It is not just these large economies, even comparable European economy like Germany has seen a spike in trade with India, which rose from USD 19 billion in 2010 to USD 27 billion in 2021.

Moreover, a significant part of the trade between India and France over the past few years has been due to the defence purchases and other government to government deals like metro rails and locomotives. If you take these out of the equation, the Indo-French trade figures collapse, indicating the commercial relationship remains very shallow and limited.

The two governments have failed to see that the commercial ties between India and France follow the same trajectory as the relationship in other spheres. This is largely because the Small and Medium Enterprises, which are the backbone of both the economies, are almost entirely missing from the trade as they continue to remain suspicious and nervous about entering the market.

It does not help matters that in areas where India is traditionally strong, pharmaceutical and farm products, besides textiles, the French market remains almost tightly closed, with Indian food exporters frequently complaining about the sudden and frequent changes in sanitary and phytosanitary norms that lead to containerloads of food exports being rejected by the French Customs.

Similarly, in pharma, not only have the French and other European countries blocked pharma goods from entering the European Union area, but also stopped goods passing through French ports to third countries, notably in Africa.

On their part, the French also complain about the closed or highly restricted Indian market, notably for French foods and wines as well as for automobiles and other sectors.

It does not help the matters that India is perceived as a very complicated place to do business, notwithstanding the now-discredited rankings of the World Bank on the so-called ease of doing business index. Numerous high-profile failures of the Indian ventures of huge French labels, be it automaker Peugeot or foods company Danone, also reinforce the fear that most French SMEs see India with.

It is telling that even in a government-backed deal, when French aircraft maker Dassault Aviation, asked its vendors, almost all of them SMEs, to look at possibilities of setting up business in India as part of the offset commitments of Dassault in the purchase of 36 Rafale fighter jets for the Indian Air Force, most of them reportedly stayed away, despite several sessions with Dassault which is also said to have offered to help them with setting up in India.

As the two nations now work for the next 25 years of their relationship, broadening and deepening bilateral trade relations and getting the SMEs to join this partnership should be the key focus.